calico journal (online) issn 2056–9017

https://doi.org/10.1558/cj.36996

. –

©,

Rock or Lock? Gamifying an online course

management system for pronunciation

instruction: Focus on English /r/ and /l/

Michael Barcomb

1

and Walcir Cardoso

2

Abstract

is one-group quasi-experimental study aimed to determine the eectiveness

of using a gamied course management system with points, badges (and con-

sequently competition) to facilitate the development of English phonology in a

foreign language context in Japan. To implement this idea, we focused on the

acquisition of English segments /r/ and /l/ in production (as in /r/ock and /l/

ock respectively). During the study, participants were asked to engage in gami-

ed pronunciation activities over a period of two weeks, using a popular learn-

ing site (Moodle). e data collection instruments included pre- and posttests

to examine the development in production of /r/ and /l/ (using controlled aural

elicitation tasks), a written follow-up questionnaire, and user logs to investigate

users’ perceptions of the pedagogy utilized. e results indicate that participants

beneted from the proposed gamied system for L2 pronunciation instruction,

as they improved their production of the target English /r/ and /l/ segments. In

addition, responses from the interviews and user logs revealed that participants

perceived using the site as enjoyable, anxiety-reducing, and pedagogically useful.

K: L ; ; -

.

Over the past two decades, research in second or foreign language (L2) pho-

nology, particularly within communicative frameworks (e.g., Celce-Murcia,

Article

Aliations

1

Concordia University, Canada.

email: [email protected]ordia.ca

2

Concordia University, Canada.

email: Walcir.Cardoso@concordia.ca

128 R L

Brinton, & Goodwin, 2010), has pushed pronunciation instruction and research

forward. e move from achieving native-like pronunciation to a focus on

more attainable goals such as the development of intelligibility and compre-

hensibility (e.g., Derwing & Munro, 2005) has enabled instructors to help

learners work toward realistic goals, as opposed to laboring toward unrealistic

objectives such as the achievement of native-like pronunciation (Levis, 2005).

While many experiments attempt to understand the process of acquiring an L2

phonological system (e.g., Saito, 2013), there is a lack of research that investi-

gates the development of young beginning learners’ L2 pronunciation—without

direct instruction from a teacher—in the foreign language setting (for examples

with adult learners in a computer-assisted environment see Fouz-González,

2019; Mompean & Fouz-González, 2016; and omson, 2011). To this end, this

paper investigates the eectiveness of using gamied pronunciation instruction

on the development of L2 phonology.

In particular, this pilot study investigates how a gamied learning environ-

ment (occasionally referred to as “site”) might contribute to the acquisition of

foreign /r/ and /l/ by a group of Japanese junior high school English learners.

e open source course management system, Moodle, was chosen because it is

amenable to gamication via user-designed plugins (e.g., leader boards; Pastor-

Pina, Satorre-Cuerda, Molina-Carmona, Gallego-Durán, & Llorens-Largo,

2015). As it will be detailed, a gamied Moodle site with pronunciation videos

has the capacity to persuade learners to study about and practice pronouncing

articulatorily dicult L2 segments. In this study, a gamied pronunciation

site, titled “English Detective”, rewarded students with points and badges as

they worked through a series of detective themed pronunciation activities. A

one-group pretest-posttest quasi-experimental design was employed to inves-

tigate the eectiveness of a gamied version of Moodle (specically designed

for this study, containing explicit pronunciation videos) on the acquisition of

two English segments, /r/ and /l/, and associated metalinguistic knowledge.

Background

Second Language Pronunciation Instruction

As has been conrmed by researchers and practitioners, pronunciation instruc-

tion is still neglected in the L2 classroom (Celce-Murcia et al., 2010; Derwing

& Munro, 2005). Currently, pronunciation research and pedagogy focus on

intelligibility as the ultimate goal of pronunciation instruction (e.g., Jenkins,

2000), within an approach that recognizes the importance of both segmen-

tal and suprasegmental aspects of L2 phonology (Celce-Murcia et al., 2010;

Jenkins, 2000). However, in foreign language contexts, access to the target

language via exposure or interaction with other L2 speakers is oen limited to

M B W C 129

the classroom, where time and resources are limited (Collins & Muñoz, 2016).

Accordingly, attention needs to be placed on how to teach pronunciation in

a way that expands opportunities for learners to develop intelligible speech

without exhausting the allotted time and resources.

One approach to pronunciation instruction is form-focused instruction,

which is described as any eort a teacher makes to help learners build implicit

or explicit knowledge about language form (Spada, 1997). Form-focused

instruction consists of a sequence of teaching strategies that include noticing,

building awareness, and then practicing the target feature (Lyster, 2007). e

rst step, noticing, is established when learners pay attention to and notice the

accurate use of certain L2 features (DeKeyser, 2007). is is of importance to

this study because the instructional pronunciation videos used in the treat-

ment (see forthcoming discussion) are specically designed to help learners

cue in on the mouth to develop explicit knowledge about how to move their

articulators to produce the target sounds: /r/ and /l/. e next step, awareness,

occurs when students receive corrective feedback as a method of raising aware-

ness during communicative activities. e third step, practice, occurs when

they communicate or produce speech, which is the time when it is important

for teachers to provide explicit corrective feedback for target features that are

particularly dicult to notice (Spada & Lightbown, 2008).

A study about the eect that form-focused instruction and corrective feed-

back have on Japanese learners’ pronunciation of English /r/ was conducted

by Saito and Lyster (2012). 65 Japanese university students learning debate

skills in English were split into two groups: while one received form-focused

instruction before communicative activities, the other received the same

form-focused instruction in addition to corrective feedback (via recasts). e

results revealed that learners who received corrective feedback in the form

of pronunciation-focused recasts outperformed the group who only received

form-focused instruction, though it showed only a slight improvement in this

instructional setting, and only in familiar lexical contexts.

To explore this nding further, Saito (2013) conducted a study where learn-

ers in one experimental group received form-focused instruction (as discussed

above), and the other experiment group received a combination of explicit pho-

netic information and form-focused instruction; the control group participated

in meaning-oriented activities that did not focus on form. Explicit phonetic

information diers from form-focused instruction because learners are speci-

cally drawing their attention to segmental L2 speech instead of lexical units

(Saito, 2013), which was hypothesized to magnify the eects of form-focused

instruction and to help learners establish new phonetic categories. Saito’s

results indicate that learners who receive both explicit phonetic information

and form-focused instruction can make improvements at pronouncing /r/ in

130 R L

both familiar and unfamiliar lexical contexts, while learners who only receive

form-focused instruction will likely fail to do so.

To deliver explicit phonetic information, Saito (2013) emphasizes provid-

ing over-exaggerated exemplars of the pronunciation of key features (e.g., lip

rounding, slow speech) to help learners notice the dierences between per-

ceptually similar sounds such as /r/ and /l/. e author grounds this deci-

sion in research that examines how speech perception contributes to learners

developing new phonetic categories to improve L2 pronunciation (e.g., per-

ceptual assimilation model: Best & Tyler, 2007; speech learning model: Flege,

1995). Accordingly, instruction needs to focus on raising perceptual noticing

of target sounds both lexically and phonetically in order to help learners create

new phonetic categories so that they can dierentiate similar sounds (Saito,

2013). In this study, digital technology was used to enhance the delivery of the

explicit phonetic information, as students cued in on the instructor’s mouth in

videos specically designed to provide explicit information before practicing

pronunciation and trying minimal pair listening quizzes.

Computer-Assisted Pronunciation Instruction

Research in computer-assisted L2 learning indicates that it can be eective

for providing opportunities to improve both knowledge of target sounds and

the pronunciation of those features. In this scenario, learners have access to

two channels of feedback—audio and visual (Hardison, 2004), which could

enhance the delivery of explicit phonetic information. Tsubota, Dantsuji, and

Kawahara (2004) explored the combination of audio and visual feedback in

an experiment that focused on autonomous pronunciation practice in a multi-

modal system that provided university students with a detailed pronunciation

report. Specically, the system identied segmental errors such as /r/ and /l/

and provided written metalinguistic information about how to produce the

target sound, which contributed to pronunciation gains.

In further evidence for digitally-based autonomous pronunciation practice,

Mompean and Fouz-González (2016) conducted a study about the pedagogical

use of Twitter, wherein participants received daily tweets that featured a target

word and information on how to pronounce it. e results indicate that the

learners autonomously improved their L2 pronunciation by the end of the treat-

ment. Another recent example of how digital environments can be eective

for pronunciation instruction is Fouz-González (2019), who provided learners

with explicit information about L2 pronunciation in class before having them

listen to a podcast with examples of the target feature. Students then practiced

the features at home on their own before doing a group pronunciation activity

in class. ese aspects of CALL based pronunciation practice are important

M B W C 131

because the use of technology in pronunciation instruction should enable

learners to practice on their own without time constraints or the pressure

associated with speaking in front of other students (Fouz-González, 2015).

One possible way of incorporating technology to deliver explicit phonetic

information is through Fogg’s (2002) captology approach, which is the use of

computing technology to persuade individuals in ways humans cannot. One

specic use, technology as a medium, is based on providing digital experiences

that make anxiety-inducing activities more approachable. For example, the use

of pronunciation videos that zoom in on the teacher’s mouth could provide key

metalinguistic information about how to produce the target sound. In a digital

space, this can be done without the pressure associated with excessive requests

by the instructor to repeat sounds, looking closely at the instructor’s mouth,

or making pronunciation mistakes in front of others. Such an approach could

extend the work of Saito (2013), as the delivery of explicit phonetic information

in instructional settings is typically only available in person. e use of digital

tools to help students visualize how to pronounce L2 features in this manner

contributes to the awareness of the target features (Lord, 2019). In sum, there is

evidence that blending explicit pronunciation instruction with digital technol-

ogy is a promising direction in research about L2 pronunciation instruction, but

an equally important aspect of digital environments is that they aord learners

opportunities to practice pronunciation in a comfortable setting of their choice.

Of interest to this study is the potential that explicit pronunciation instruc-

tion has to reduce language anxiety. L2 metaphonological awareness is a

specic type of metalinguistic skill that focuses on L2 pronunciation (e.g.,

Celce-Murcia et al., 2010; Saito, 2013) and includes activities such as teaching

students how to position their articulators to produce a specic segment. In the

process, learners can take a more reective and playful approach to pronounc-

ing problematic L2 features (Szyszka, 2017). Szyszka stresses that this type of

explicit pronunciation strategy enables the learner to take an approach that

reduces anxiety by increasing ownership in developing skills that protect them

from future embarrassment caused by pronunciation errors. is indicates

that providing explicit phonetic information in a digital setting equipped with

gamied elements could potentially help learners to practice pronunciation

in a more comfortable way.

Gamied Learning Environments in L2 Acquisition

e notion of digital games serving as a space for learning is well documented

(e.g., Bogost, 2011; Gee, 2007). Gamication, however, is dierent from video

games because it utilizes video game elements (not games) to motivate users to

engage in learning activities (Deterding, Dixon, Khaled, & Nacke, 2011). Gami-

cation includes elements from games such as avatars, feedback, levels (and

132 R L

consequently competition) under explicit and enforced rules, and teamwork

(Reeves & Read, 2009). Hamari, Koivisto, and Sarsa (2014) explain that when

motivational aordances such as points are earned, a psychological response

is triggered, which, in turn, triggers a specic behavioral outcome such as

pronunciation practice.

In L2 learning, Reinhardt (2019) proposes a framework to examine research

and practice in digital games, which includes three distinct types: game-

enhanced, game-based, and game-informed. e authors explain that game-

enhanced materials include o the shelf games not designed for language

learning, while game-based materials take advantage of game play for educa-

tional purposes. e third type, game-informed materials, includes elements

of games that can be used to enhance L2 teaching and learning, which includes

gamied approaches. Of importance to this study is that Reinhardt (2019)

stresses that it is possible to utilize game-informed materials to investigate a

research problem from the perspective of L2 pedagogy and/or the perspective

of the learner. In line with this, the present study aims to inform L2 pronuncia-

tion research by emphasizing a comfortable and fun environment to develop

explicit phonetic knowledge and practice pronunciation.

A popular example of gamication in language learning can be found in the

app, Duolingo, which enables learners to earn points and badges as they work

through levels on their own, completely free of a pedagogical context. To test

the eectiveness of the app in a pedagogical setting, Rachels and Rockinson-

Szapkiw (2018) investigated how Duolingo could be used to contribute to the

acquisition of vocabulary and grammar in L2 Spanish. While one group of

students completed lessons on the app, the other covered comparable materi-

als in a classroom setting. e results indicated that there was no dierence

between the two groups in regard to gains, demonstrating that this type of

technology is useful for L2 instruction. It is possible that the participants in

both groups performed comparably because they both received grammar-

translation style instruction. While this can be eective in some instances

(e.g., for learning vocabulary and morphosyntax), we do not believe it would

be as benecial for pronunciation instruction.

For a more comprehensive and inclusive approach to L2 pedagogy, Rein-

hardt (2019) recommends the use of “smaller, limited games and educa-

tional apps that utilize some game mechanics” (p. 7) in order to create a more

learning-oriented system. We believe that open source course management

systems like Moodle can be adapted to full this recommendation, as they are

easily accessible to and commonly used by L2 teachers. Importantly, Moodle

can be gamied to trigger responses via the following elements: progressive

learning (e.g., via maps, levels); socialization (e.g., when students collaborate

on missions, send messages); feedback (e.g., instant feedback, progress bars);

M B W C 133

and rewards (e.g., coins, badges, leaderboards; Pastor-Pina etal., 2015). In this

way, many typical elements of a Moodle page (e.g., conditions to access, chats),

if combined with user-designed gamied-plugins to create leaderboards and

reward systems, may contribute to pronunciation practice. Of further interest

is that programming knowledge is not necessary to create such a system, which

can instead be created through the customization of open source materials

(Barcomb, Grimshaw, & Cardoso, 2017, 2019). is could enable more teach-

ers to explore the use of gamied materials to enable students to practice

pronunciation outside of class.

Research on the use of digital games in L2 pedagogy indicates that the role

of the teacher and the location in which learners study can take on many dif-

ferent forms. For example, Sauro and Zourou (2019) explain that the “digital

wilds” include online language learning environments that are completely

independent of a pedagogical institution and can include activities such as

using a second language to play a video game online with other users. In

line with this, Sundqvist (2019) reports that Swedish secondary students who

played English commercial games on their own online outperformed those

who self-identied as infrequent users or non-gamers in recognizing and using

L2 English vocabulary. Given that games and gamied learning environments,

as discussed above, expand opportunities for language learning on-the-go,

teachers may decide to incorporate such environments in pedagogical settings.

In specic, at-home teacher-initiated materials (Sundqvist & Sylvén, 2016) are

teacher-selected online language learning materials that students can use out-

side of class. An example of this can be seen in Newgarden and Zheng’s (2016)

study, in which the researchers replaced a semester-long ESL course with the

commercial game World of Warcra. Participants completed missions in the

game with other classmates and the teacher once per week beyond the walls

of an institution by using text-chats and video conferencing soware to com-

municate with each other. Instead of adapting a commercial game to expand

language learning opportunities beyond the walls of the language classroom,

the current study examines a game-informed/gamied system that could be

implemented as an online resource in an at-home teacher-initiated setting.

The Present Study

is study examined the pedagogical use of an online gamied pronunciation

site to aid Japanese junior high school students in the production of /r/ and /l/

by enhancing their explicit understanding of these segments. is population

was chosen because research indicates that the foreign language classroom in

Japan provides limited opportunities for pronunciation practice (e.g., Machida,

2016). is scenario is further complicated by Japan’s Ministry of Education’s

attempt to implement high-level linguistic activities, such as debates, into all

134 R L

classrooms (MEXT, 2014). is pilot study aims to propose a way to alleviate

these constraints by enabling students to study L2 pronunciation online.

e target segments /r/ and /l/ were chosen because Japanese learners have

diculty acquiring them in both perception (e.g., Lively, Logan, & Pisoni,

1993) and production (e.g., Larson-Hall, 2006). Japanese L1 learners also have

diculties dierentiating /r/ and /l/ and instead perceive it as the Japanese

tap, which is situated in a space between /l/, /r/, and /d/ (Hattori & Iverson,

2009). Finally, these two segments are of interest because they carry a high

functional load, as dened by Brown (1988) and Celce-Murcia et al. (2010);

that is, they are highly productive in English and serve to dierentiate many

highly frequent words in the language.

e following research questions were designed to address the goals of this

mixed-methods study, which explored the use of a gamied online pronun-

ciation environment to facilitate the development of /l/ and /r/ in a foreign

language context in Japan. To determine the eectiveness of the proposed

approach to teaching pronunciation, we have developed the following research

question: What are the eects of the proposed gamied environment on the

pronunciation of the /r/-/l/ distinction among Japanese learners of English?

e question can be subdivided into three sub-components:

•

Does the proposed gamied environment contribute to improved pro-

nunciation of /r/ and /l/?

•

Does the proposed gamied environment facilitate increased awareness

of the /r/-/l/ distinction?

•

What are users’ perceptions of learning pronunciation in the proposed

gamied environment?

Method

is one-group pretest posttest study took place in a gamied Moodle site and

lasted for two weeks. It aimed to answer the rst component of the overarching

research question quantitatively with tests to determine if our proposal can

improve learners’ production of /r/ and /l/. Aer participants nished their

nal pronunciation test, they completed a posttest follow-up questionnaire that

gathered qualitative data in the form of written responses to better understand

the second and third components of the research question. e data include

responses related to how participants perceived their explicit phonetic aware-

ness was facilitated by pronunciation videos, how they perceived gamication

(in general), and how they perceived the gamied site, including its ability to

reduce anxiety and promote learning. e research design is illustrated in

Figure 1.

M B W C 135

Figure 1. Research design.

Participants

e study included 11 Japanese junior high school students living

in Japan (female: 7; male: 4) with a mean age of 13.7 (SD=1.7),

all participating from home and interacting with the main

researcher via a popular videoconferencing application; they

were told that they would participate in a video game-like class

to practice English using the video and audio functions of their

iPads or laptop computers. Participants were recruited through

learning centers, blogs, and online groups dedicated to learning

English (i.e., they were not in an intact class). All 11 students who

started the study completed it through the posttests, although

participation was voluntary, and they were not compensated for

their participation. e entire study was conducted online.

Instruments

To determine whether the proposed gamied environment contributed to

improved pronunciation of /r/ and /l, students took a 38-item pronunciation

pretest and posttest that included 28 target simple /r/ and /l/ words distributed

in onset (word-initial; e.g., /r/ice, /l/ate) and coda positions (word-nal; e.g.,

poo/r/, mai/l/). e remaining 10 items were distractors that contained neither

/r/ nor /l/ (e.g., big). A breakdown of the items used in the study is shown in

Figure 2.

e participants were asked to produce the target words in both isolation

(e.g., /r/ain) and inserted at the beginning of short pause-initial sentences (e.g.,

/r/ain, I like that!). ey completed a listen-and-repeat test that involved watch-

ing video recordings of either words or brief sentences before recording them-

selves saying the word or phrase that they heard. e pretests and posttests

were both done at home via Moodle, which was designed to provide learners

a comfortable place to do the assignments and reduce the observer’s paradox

(i.e., the participants’ discomfort in being observed, which may aect their

linguistic output; Labov, 1972). e accuracy of /r/ and /l/ pronunciation was

assessed as accurate or inaccurate by one of the researchers (a native English

speaker) and one assistant (a uent English speaker of Japanese origin). When

136 R L

the raters disagreed on an item (which rarely happened), a third researcher

was asked to make a determination. If students produced /l/ instead of /r/, or

instead produced the Japanese tap (i.e., /ɾ/), then the item was deemed to be

inaccurate. ere were 28 /r/ and /l/ items (14 of each) on the pre- and posttest.

Qualitative data were collected to understand how learners perceived the

pronunciation videos aected their awareness of the target features, and how

the proposed gamied environment (including its anxiety-reducing benets)

contributed to learning. ese data were collected in the form of an eight-item

written follow-up questionnaire that asked open-ended questions in Japanese:

(1) What was the strength of the site to learn English? (2) What do you like

about this site? (3) What was the weakness of this site to learn English? (4)

What would you change about this site? (5) Aer learning with the site, do

you feel that you are more comfortable speaking English in front of your class?

(6) Do you feel that you learned English from the site? (7) Would you like this

site if it was part of your school curriculum? And (8) How do you feel about

learning English from videos? ese eight questions required open-ended

responses about how the participants perceived learning pronunciation on

the site and what they liked or did not like about the pedagogical experience.

e questionnaire was completed online and was located in a link found in

English Detective. e written responses (completed in Japanese but translated

into English for analysis) were coded according to the themes that informed

the qualitative analysis: the development of an explicit phonetic understand-

ing of target features in a digital context, and participants’ perceptions of the

gamied site, including its ability to reduce anxiety and promote learning.

Figure 2. Pronunciation materials.

M B W C 137

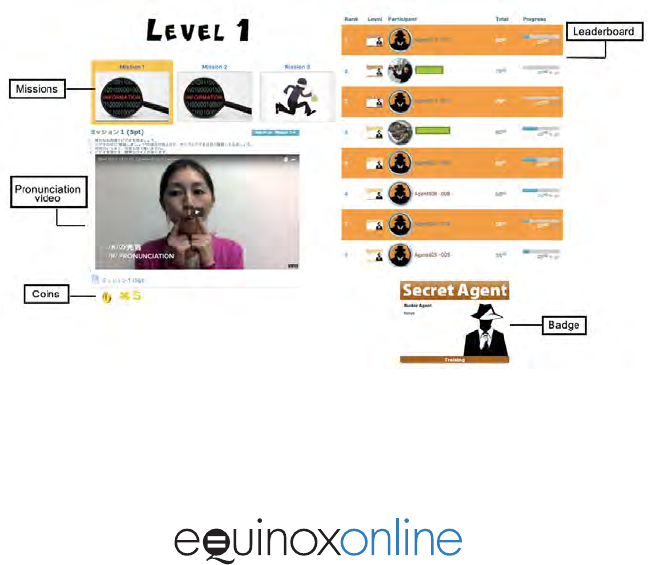

English Detective: A gamied Moodle site

English Detective is a gamied Moodle site that was built specically for this

study. To encourage learners to practice L2 pronunciation in an environment

less likely to trigger anxiety, activities were completed in the form of gami-

ed missions. Participants received experience points for each mission they

attempted, which automatically went to a leaderboard and subsequently opened

the next mission. is was done through a leaderboard plugin in Moodle, Level

Up!, which housed many of the gamied elements in this treatment. e lead-

erboard, which can be seen with other elements in Figure 3, was orchestrated

to provide experience points in the form of coins for each activity, show each

participant’s avatar, display the total number of coins, update badges, and

inform the students of the number of coins necessary for the next badge.

As a strategy to compete, participants were instructed to review materials in

order to receive additional coins and, thus, higher ranking badges. For every

20 coins, participants earned a new badge, ranging from Rookie Agent to Super

Agent. To deemphasize failure, the coins and leaderboard represented “experi-

ence points”, which means the coins reected attempts, not mastery. Because

the target feature was a hard-to-acquire segment and therefore beyond the

learner’s immediate control, the goal was to deemphasize failure and instead

reward learners for their eort and continued practice (e.g., Bell, 2018). Each

student used the site for approximately one hour by the end of the study. To pre-

vent participants from receiving coins for constantly doing the same mission,

a lter required 20 minutes to pass before earning points for the same activity.

Figure 3. Overview of the gamied pronunciation site.

138 R L

Mission 1 consisted of videos that provided learners with explicit instruc-

tion and multiple opportunities to practice the pronunciation of /r/ and /l/

in onset position. In line with Saito (2013), the videos provided metalinguis-

tic cues to visually draw the learner’s attention to the relevant articulators

(e.g., the positioning of the tongue tip against the alveolar ridge to produce

/l/). To relax, students were instructed to massage their faces to prepare

themselves to make foreign sounds. To deliver information about how to

produce these sounds, an L1 speaker of Japanese with experience teaching

EFL served as the teacher in the videos and delivered relevant metalinguistic

information about the features before pronouncing a few words; a native

English speaker also provided examples of how to pronounce each sound.

In the /l/-related videos, students were instructed to touch their tongue to

the alveolar ridge (i.e., “the hard bump on the roof of the mouth”), while

for /r/ production, the videos focused on lip rounding and preventing the

tongue from touching the alveolar ridge, according to Celce-Murcia et al.’s

(2010) recommendations.

As a pedagogical strategy, participants were instructed that, if they saw

the teacher’s tongue in the video, that meant /l/ was produced. For the pro-

nunciation of /r/, learners were instructed to focus on lip rounding and to

avoid touching their tongue to the alveolar ridge. Per Fogg’s (2002) recom-

mendations, the video instructed learners to rewind and pause the video to

practice pronouncing the words and to study the instructor’s articulators for

each segment. e activity was designed to provide access to a form of explicit

phonetic information not available in classroom instruction. Students were

also instructed to pause the video to review wordlists with the target feature

before pressing play to listen to the instructor’s pronunciation. An optional

activity in Mission 1 gave participants the opportunity to use tablets to draw

a picture of what a person’s mouth looks like when pronouncing /l/ or /r/

(see Figure 4).

Mission 2 followed the same format as Mission 1, except that it focused on

the production of /l/ and /r/ in coda position (e.g., poo/r/, mai/l/).

Mission 3 gave learners an opportunity to practice the skills learned in

the rst two missions by completing a minimal-pair listening quiz. e

rationale for including a listening quiz comes from ndings that suggest

that these tasks can improve oral production (Bradlow, Pisoni, Akahane-

Yamada, & Tohkura, 1997) and may even reduce anxiety by giving learners

an opportunity to focus on target sounds without the pressures associated

with language production (Celce-Murcia et al., 2010). Perception activities

also serve as an opportunity for learners to exercise their explicit phonetic

understanding of the target features, which can contribute to pronuncia-

tion gains (Saito, 2013). Six questions quizzed learners on their ability to

M B W C 139

dierentiate minimal pairs (e.g., “lip” and “rip”). Half of the questions

showed a video of the researcher pronouncing the word so that participants

could visually notice the target feature, and the other half were audio only.

Aer viewing and/or listening to each item, participants selected /r/ or /l/

based on which sound they heard.

Analysis of Results

e data from the pronunciation tests were analyzed using descriptive sta-

tistics. Initially, a composite score for /l/-/r/ pronunciation was calculated in

order to determine the eectiveness of the treatment on the pronunciation of

perceptually similar segments. To better understand the eect of the treatment

on each individual segment, a separate set of analyses was conducted.

e short-answer follow-up questionnaire data were analyzed with the help

of one research assistant, according to the coding methods proposed by Saldaña

(2009): the participants’ responses were rst categorized based on learners’

reported experiences, that is, their perception of learning pronunciation in

a gamied site with respect to its strengths and weaknesses as a pedagogical

tool. ese were then broken into subcomponents according to the themes

that informed the analysis: the eects of the proposed site on (1) developing

an explicit phonetic understanding of /r/-/l/, (2) reducing anxiety, and (3) pro-

moting learning. In vivo coding was chosen as the coding method to represent

participants’ intended meanings (i.e., sections of data were assigned a label

such as “developing explicit phonetic awareness”). ese data were extracted

verbatim from the data set and inserted into columns in a spreadsheet to create

themes, categories, and sub-categories for the qualitative analysis.

Results

Quantitative

All participants began and completed the study through the posttests and, by

the end, completed all proposed activities at least once and spent a mean total

of 63.23 minutes in the gamied site, SD= 24.82, 95% CI [46.72, 80.22]. To rst

determine the eectiveness of the gamied environment on the production

of /r/ and /l/ as a composite score, a Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test was used to

measure the accuracy of their pronunciations. e key assumption for the test,

the distributional assumption, was not violated, as assessed by a histogram

with a superimposed normal curve on the distribution of scores. e results in

Table 1 indicate that there was a statistically signicant increase in /r/ and /l/

accuracy (Mdn = 8) on the posttest (Mdn = 19) when compared to the pretest

(Mdn = 11),z= 2.97,p= .003.

140 R L

Table 1

Composite /r/ and /l/ Results (z-scores)

Pretest Post

Outcome Mdn Mdn n z

/r/ & /l/ items 11.00 19.00 11 2.97*

* p < .05. Mdn = Median

To better understand the effect of the treatment on the pronuncia-

tion of /r/ and /l/, each segment was analyzed separately by conducting

a pair of related-samples Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (Table 2). The key

assumption for the test, the distributional assumption, was not violated,

as assessed by a histogram with a superimposed normal curve on both

/r/ and /l/ distributions.

Table 2

Individual /r/ and /l/ Results (z-scores)

Pretest Post

Outcome Mdn Mdn n z

/l/ items 5.00 10.00 11 2.94*

/r/ items 6.00 10.00 11 2.81*

* p < .05. Mdn = Median

Regarding the pronunciation of /l/, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test determined

that there was a statistically signicant median increase in the number of

correct /l/ items from the pretest (Mdn = 5 correct /l/ items) to the posttest

(Mdn = 10 correct /l/ items), z = 2.94, p < .05. Similar to the composite score,

a Wilcoxon signed-rank test for /r/ pronunciation determined that there was

a statistically signicant median increase in the number of correct /r/ items

from the pretest (Mdn = 6 correct /r/ items) to the posttest (Mdn = 10 correct

/r/ items), z = 2.81, p < .05. Altogether, these ndings indicate that the par-

ticipants beneted from the gamied Moodle site, as learners appear to have

equally improved in their production of English /r/ and /l/.

Qualitative

To answer the second and third subcomponents of the research question, which

examined (1) whether the proposed learning environment led to an increase

in phonetic awareness of the /r/-/l/- distinction and (2) the participants’

M B W C 141

perceptions of the gamied learning environment, participants completed a

posttest written questionnaire consisting of eight open-ended questions, as

described earlier.

e analysis of the participants’ responses suggests they developed explicit

knowledge of /r/ and /l/ by: (1) noticing segments that do not exist in their L1

(e.g., “I could learn about sounds that do not exist in Japanese”); (2) learning

how to manipulate their articulators (e.g., “I can pronounce sounds correctly

by focusing on my tongue, mouth, and lips”); (3) dierentiating contrasting

sounds (e.g., “I feel that I learned the /r/ and /l/ dierence”); and (4) developing

explicit phonetic knowledge in both perception and production (e.g., “I can

hear and practice correct pronunciation”).

To further understand the development of explicit phonetic awareness from

a qualitative perspective, the drawing activity provides key insights. Of the

seven students who completed the activity, all focused on ensuring their draw-

ing showed the tongue tip touching the alveolar ridge for /l/ and a low and

drawn back tongue for /r/. Figure 4 illustrates an example of a typical draw-

ing produced by the participants, indicating their awareness of the tongue

positioning for /l/.

Figure 4. An example of a student’s depiction of one’s articulators when producing /l/.

An interview question about how participants perceived learning from

videos yielded responses that were directly related to the aordances of per-

suasive technology (Fogg, 2002), which indicates that this strategy may have

142 R L

been eective for delivering explicit phonetic information. For instance, six

learners stated that they were comfortable with closely analyzing the teacher’s

mouth in the video to build explicit knowledge about the target L2 pronuncia-

tion (e.g., “I can see the shape of the mouth”; “videos allowed me to watch the

movement of the tongue and mouth”). Furthermore, six responses indicated

that, in line with the aordances of persuasive technology, learners paused and

replayed the videos to study each feature (e.g., “I can hear native speaker sounds

as many times as I want and still be able to repeat to practice”). An analysis

of the log data supports that students viewed the videos several times: those

related to /l/-/r/ in onset position were watched 70 times, and those involving

the coda were viewed 59 times.

Based on the assertion that metalinguistic approaches to pronunciation

instruction can reduce anxiety (Szyszka, 2017), and that pronunciation anxi-

ety in the L2 classroom is negatively correlated with WTC (Baran-Łucarz,

2014), one of the interview questions asked the students: “Aer learning

with the site, do you feel that you are more comfortable speaking English

in front of your class?” Seven participants responded that they felt more

relaxed about speaking English in front of their classmates (e.g., “I am more

relaxed because I understand the pronunciation a little more”; “I am more

relaxed because I can pronounce a little better”). Interestingly, these quotes

provide some preliminary evidence that participants experienced at least

some sense of relaxation as a result of having a better understanding of L2

pronunciation.

Overall, participants reported that they enjoyed the site, particularly

because it involved the assignment of coins and intrinsic competition (n=3),

or watching videos to gain points to compete (n=7). In response to the ques-

tion about the perceived weaknesses, ve of the responses were related to the

interface being in English. e other most common issue reported was that

the videos did not always load properly (n=3).

Discussion and Concluding Remarks

e goal of this study was to examine the pedagogical eectiveness of a gamied

online site with pronunciation videos to aid the development of the L2 segments

/r/ and /l/ and related explicit phonetic awareness by a group of Japanese EFL

learners. Our ndings provide quantitative evidence that the proposed peda-

gogical approach contributed to the development of English /l/ and /r/ over

the treatment period. is nding conforms with Saito (2013), who reported

pronunciation improvements in /r/-/l/ production when participants received

a combination of form-focused instruction and explicit phonetic information.

e results also conform with Saito (2013) with regard to explicit phonetic

M B W C 143

information aiding the production of /l/ and /r/, as the instructional videos

provided an explicit (oen exaggerated) pronunciation of the target features.

In addition to the quantitative evidence oered, the qualitative data suggest

that some students developed explicit phonetic awareness, likely aided by the

pronunciation videos; consequently, they felt less anxious aer completing the

experiment, thus conrming Fogg’s (2002) assumption that using technology

as a medium can make anxiety-inducing activities more approachable—devel-

oping explicit phonetic information and practicing pronunciation in the case of

this study. Furthermore, unlike the classroom learners in Baran-Łucarz (2014)

who experienced pronunciation anxiety, it appears that the digital environ-

ment in this study enabled some participants to practice pronunciation in a

more comfortable way.

Practicing pronunciation while being rewarded with experience points in

a gamied environment may have also contributed to helping learners detect

progress and persevere at learning about and pronouncing the target segments,

as evidenced by the fact that all participants completed the assigned quizzes

at least once and watched the pronunciation videos for a total of 129 times.

is nding is consistent with Hitosugi, Schmidt, and Hayashi (2014), who

reported instances of deep cognitive development by participants learning L2

vocabulary in a game-based system that also aorded them chances to replay

“learning missions” as frequently as necessary.

Despite the promise that this study shows in regard to facilitating the

acquisition of L2 phonology, there are a number of limitations that should be

acknowledged. e rst relates to the lack of a control group, which prevents

us from drawing specic conclusions regarding the optimistic results obtained.

Two other methodological limitations are the short duration of the experi-

ment (participants spent roughly one hour in the course), and the absence of

delayed posttests, which would allow us to determine if the observed improve-

ments aected learners’ long-term phonological inventory. Furthermore, the

study employed a written questionnaire to examine metalinguistic knowl-

edge. Although this instrument provided invaluable information about the

participants’ awareness to the articulation of /r/-/l/, a more rened qualitative

approach is necessary. In future studies, the development of qualitative instru-

ments should be guided by the literature on explicit phonetic awareness and

pronunciation anxiety to appropriately probe into responses related to the

development of explicit knowledge of the target features. Finally, the analysis

of the qualitative data was directed by the research questions, which means

that the themes were pre-determined and did not emerge as part of the data

analysis. Future versions of the study require more rened qualitative measures

such as interviews and focus group discussions.

144 R L

In terms of phonological gains, measuring the mere accuracy of /r/ or /l/ pro-

duction in all prosodic contexts does not provide a full picture of its acquisition.

Whether participants improved more on onsets or codas is valuable information

because, as based on the syllable structure of L1 Japanese, which only allows CV

(coda-less) sequences, it is likely that word-nal consonants will prove to be more

dicult and, therefore, possibly more anxiety inducing than onsets. Finally, for

reliability in pronunciation rating, future versions of this study will need multiple

raters and the subsequent calculation of interrater reliability.

Although pilot studies do not guarantee the success of a future experi-

ment, they are a critical rst step toward understanding which aspects of a

treatment to include in future iterations; this study does make a compelling

case to include many of its features in a follow-up study, especially with the

inclusion of a control group and more comprehensive methods that can shed

light on the eectiveness of digital gamication in the acquisition of hard-to-

acquire L2 phonological features. is study is a rst step toward determining

that L2 pronunciation techniques within a gamied setting is not only feasible

in terms of design and implementation, but also potentially facilitative of L2

pronunciation.

About the Authors

Michael Barcomb is a Phd candidate (ABD) in Education (specialization in

Applied Linguistics) at Concordia University. His research interests include the

use of games and gamication in L2 pedagogy and the role of teachers as CALL

designers.

Walcir Cardoso is a Professor of Applied Linguistics at Concordia University.

He conducts research on the L2 acquisition of phonology, morphosyntax and

vocabulary, and the eects of computer technology (e.g., clickers, text-to-speech

synthesizers, automatic speech recognition) on L2 learning.

References

Baran-Łucarz, M. (2014). e link between pronunciation anxiety and willingness to com-

municate in the foreign-language classroom: e Polish EFL context.Canadian Modern

Language Review,70(4), 445–473. ttps://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.2666

Barcomb, M., Grimshaw, J., & Cardoso, W. (2017). I can’t program! Customizable mobile

language-learning resources for researchers and practitioners. Languages, 2(3). https://

doi.org/10.3390/languages2030008

Barcomb, M., Grimshaw, J.,& Cardoso, W. (2019). Foreign language teachers as instruc-

tional designers: Customizing mobile assisted language learning technology. In Y.

Zhang & D. Cristol (Eds.),Handbook of Mobile Teaching and Learning(pp. 1–16). Berlin,

Germany: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-41981-2_130-1

M B W C 145

Bell, K. (2018). Game on! Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Best, C., & Tyler, M. (2007).Nonnative and second-language speech perception: Common-

alities and complementarities. In O. Bohn & M. Munro (Eds.),Second language speech

learning: e role of language experience in speech perception and production (pp. 13–34).

Amsterdam, e Netherlands: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.17.07bes

Bogost, I. (2011).How to do things with videogames. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota

Press. https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816676460.001.0001

Bradlow, A., Pisoni, D., Akahane-Yamada, R., & Tohkura, Y. (1997). Training Japanese

listeners to identify English /r/ and /l/: IV. Some eects of perceptual learning on speech

production. e Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 101(4), 2299–2310. https://

doi.org/10.1121/1.418276

Brown, A. (1988). Functional load and the teaching of pronunciation.TESOL Quarterly,

22(4), 593–606. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587258

Celce-Murcia, M., Brinton, D., & Goodwin, J. (2010). Teaching pronunciation: A reference

for teachers of English to speakers of other languages. New York, NY: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

Collins, L., & Muñoz, C. (2016).e foreign language classroom: Current perspectives and

future considerations.e Modern Language Journal, 100(1), 133–147. https://doi.org

/10.1111/modl.12305

DeKeyser, R. (2007).Practice in a second language: Perspectives from applied linguistics

and cognitive psychology. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org

/10.1017/CBO9780511667275

Derwing, T., & Munro, M. (2005). Second language accent and pronunciation teaching:

A researchbased approach.TESOL Quarterly,39(3), 379–397. https://doi.org/10.2307

/3588486

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to

gamefulness: Dening gamication. In A. Lugmayr (Ed.), Proceedings of the 15th Inter-

national Academic MindTrek Conference (pp. 9–15). New York, NY: ACM. https://doi

.org/10.1145/2181037.2181040

Flege, J. (1995). Second language speech learning: eory, ndings, and problems. In W.

Strange (Ed.), Speech perception and linguistic experience: Issues in cross-language

research (pp. 233–276). Timonium, MD: York Press.

Fogg, B. (2002). Persuasive technology: Using computers to change what we think and do.

San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufman. https://doi.org/10.1145/764008.763957

Fouz-González, J. (2015) Trends and directions in computer-assisted pronunciation train-

ing. In J. W. Mompean and J. Fouz-González (Eds.), Investigating English pronuncia-

tion. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137509437_14

Fouz-González, J. (2019). Podcast-based pronunciation training: Enhancing FL learners’

perception and production of fossilized segmental features. ReCALL, 31(2), 150– 169.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344018000174

Gee, J. (2007).Good video games+ good learning: Collected essays on video games, learning,

and literacy. New York, NY: Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/978-1-4539-1162-4

Hamari, J., Koivisto, J., & Sarsa, H. (2014). Does gamication work? A literature review of

empirical studies on gamication. In R. Sprague (Ed.), Proceedings 47th Hawaii Inter-

national Conference on System Sciences (pp. 3025–3034). Los Alamitos, CA: IEEE.

https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2014.377

Hardison, D. (2004). Generalization of computer-assisted prosody training: Quantitative

and qualitative ndings. Language Learning & Technology, 8(1), 34–52.

146 R L

Hattori, K., & Iverson, P. (2009). English/r/-/l/ category assimilation by Japanese adults:

Individual dierences and the link to identication accuracy.e Journal of the Acous-

tical Society of America,125(1), 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.3021295

Hitosugi, C., Schmidt, M., & Hayashi, K. (2014). Digital game-based learning in the L2

classroom: e impact of the UN’s o-the-shelf videogame, Food Force, on learner

aect and vocabulary retention. CALICO Journal, 31(1), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.11139

/cj.31.1.19-39

Jenkins, J. (2000).e phonology of English as an international language. Oxford, England:

Oxford University Press.

Labov, W. (1972).Sociolinguistic patterns. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Larson-Hall, J. (2006). What does more time buy you? Another look at the eects of long-

term residence on production accuracy of English /r/ and /l/ by Japanese speakers.Lan-

guage and Speech,49(4), 521–548. https://doi.org/10.1177/00238309060490040401

Levis, J. (2005). Changing contexts and shiing paradigms in pronunciation teach-

ing.TESOL Quarterly,39(3), 369–377. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588485

Lively, S., Logan, J., & Pisoni, D. (1993). Training Japanese listeners to identify English /r/

and /l/. II: e role of phonetic environment and talker variability in learning new per-

ceptual categories.e Journal of the Acoustical Society of America,94(3), 1242–1255.

https://doi.org/10.1121/1.408177

Lord, G. (2019). Incorporating technology into the teaching of Spanish pronunciation. In

R. Rao (Ed.), Key issues in the teaching of Spanish pronunciation: From description to

pedagogy. New York, NY: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315666839-11

Lyster, R. (2007).Learning and teaching languages through content: A counterbalanced

approach. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.18

Machida, T. (2016). Japanese elementary school teachers and English language anxiety.

TESOL Journal, 7(1), 40– 66. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.189

MEXT. (2014). English education reform plan corresponding to globalization. Retrieved

from: https://www.mext.go.jp/en/news/topics/detail/__icsFiles/aeldle/2014/01/23

/1343591_1.pdf.

Mompean, J., & Fouz-González, J. (2016). Twitter-based EFL pronunciation instruction.

Language Learning & Technology, 20(1), 166–190.

Newgarden, K., & Zheng, D. (2016). Recurrent languaging activities in World of Warcra:

Skilled linguistic action meets the Common European Framework of Reference.

ReCALL, 28(3), 274–304. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344016000112

Pastor-Pina, H., Satorre-Cuerda, R., Molina-Carmona, R., Gallego-Durán, F., & Llorens-

Largo, F. (2015). Can Moodle be used for structural gamication? In L. Chova, A. Mar-

tinez, & I. Torres (Eds.), Proceedings of INTED 2015 (pp. 1014–1022). Madrid, Spain:

IATED.

Rachels, J., & Rockinson-Szapkiw, A. (2018). e eects of a mobile gamication app on

elementary students’ Spanish achievement and self-ecacy.Computer Assisted Lan-

guage Learning,31(1–2), 72–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2017.1382536

Reeves, B., & Read, J. (2009). Total engagement. Using games and virtual worlds to change

the way people work and businesses compete. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Reinhardt, J. (2019).Gameful second and foreign language teaching and learning: eory,

research, and practice.Basingstoke, England: Palgrave-Macmillan. https://doi.org/10

.1007/978-3-030-04729-0

Saito, K. (2013). Reexamining eects of form-focused instruction on L2 pronunciation

development.Studies in Second Language Acquisition,35(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10

.1017/S0272263112000666

M B W C 147

Saito, K., & Lyster, R. (2012). Eects of formfocused instruction and corrective feedback

on L2 pronunciation development of /ɹ/ by Japanese learners of English.Language

Learning,62(2), 595–633. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2011.00639.x

Saldaña, J. (2009). e coding manual for qualitative researchers. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Sauro, S., & Zourou, K. (2019). What are the digital wilds?Language Learning & Technol-

ogy, 23(1), 1–7.

Spada, N. (1997). Form-focussed instruction and second language acquisition: A review

of classroom and laboratory research.Language Teaching,30(2), 73–87. https://doi.org

/10.1017/S0261444800012799

Spada, N., & Lightbown, P. M. (2008). Formfocused instruction: Isolated or inte-

grated?TESOL Quarterly,42(2), 181–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1545-7249.2008

.tb00115.x

Sundqvist, P. (2019). Commercial-o-the-shelf-games in the digital wild and L2 learner

vocabulary. Language Learning & Technology, 23(1), 87–113.

Sundqvist, P., & Sylvén, L. (2016).Extramural English in teaching and learning. London,

England: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-46048-6

Szyszka, M. (2017). Pronunciation learning strategies and language anxiety: In search of an

interplay. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-50642-5

omson, R. (2011). Computer assisted pronunciation training: Targeting second language

vowel perception improves pronunciation. CALICO Journal, 28(3), 744–765. https://doi

.org/10.11139/cj.28.3.744-765

Tsubota, Y., Dantsuji, M., & Kawahara, T. (2004). Practical use of Autonomous English

pronunciation learning system for Japanese Students. Proceedings of the Symposium on

Computer Assisted Learning (pp. 1–4). Venice, Italy: INSTiL04.