The Australian Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong

Room 302, 3/F, Lucky Building, 39 Wellington Street, Central, Hong Kong

Tel: (852) 2522 5054 Fax: (852) 2877 0860

austcham@austcham.com.hk www.austcham.com.hk

Tax Treaties Branch

Corporate and International Tax Division

Treasury

Email: TaxTreatiesBranch@treasury.gov.au

15 April 2024

Dear Sir or Madam,

Submission on Australia’s Tax Treaty Network Expansion

The Australian Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong (AustCham) represents more than 800 members

from 245+ companies. We are one of the largest international chambers in Hong Kong and one of the

largest Australian chambers abroad. AustCham’s membership includes Australian businesses

operating offshore, Hong Kong companies with significant investments in Australia, international

companies with operations in Australia and Hong Kong, and individuals leading Small and Medium

Sized businesses and working for global business in Hong Kong. AustCham has been in Hong Kong

since 1987 supporting our members, their business and the Australia-Hong Kong bi-lateral

relationship.

The Treasury’s consultation seeking views on issues related to Australia’s tax treaty network provides

an opportunity to once again share AustCham’s support for expanding Australia’s tax treaty network

by considering a comprehensive Double Tax Agreement (DTA) between Australia and Hong Kong.

Hong Kong is home to over 100,000 Australian nationals, with the largest number of Australian

businesses based outside Australia and our second largest expatriate community globally. As of 2023,

there were 27 regional headquarters, 52 regional offices and 80 local offices in Hong Kong with parent

companies located in Australia – the 10th largest international representation of international regional

headquarters in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong is a global financial centre and Asia’s leading finance hub. It is a major logistics and

transportation hub and remains the gateway to and from China and the wider North Asia region

(including Japan, Korea and Taiwan) for investment and capital flows. North Asia accounts for the

largest proportion of Asian trade with the rest of the world. Hong Kong is a key trade partner to

Australia and is the country’s 11

th

largest source of direct foreign investment. A DTA with Hong Kong

will allow alignment and consistency with how Australia treats its major trading and investment

partners.

Hong Kong has 48 DTAs in place with jurisdictions that include Australian tax treaty partners such as

the United Kingdom, Singapore, New Zealand, Japan, Indonesia and Malaysia. As an example, Hong

Kong and New Zealand signed a tax treaty in December 2010, which entered into force in November

2011. Hong Kong is also currently in DTA negotiations with 17 other jurisdictions, including Germany,

Israel and Norway. We understand the Hong Kong government is very receptive to entering into DTA

negotiations with Australia.

A DTA between Australia and Hong Kong is critical for Australian business and important in

strengthening the relationship between Australia and Hong Kong. Such an agreement fosters

increased cross-border trade and investment between the two jurisdictions and secure economic

growth into the future, whilst demonstrating a shared commitment to addressing international tax

avoidance practices.

The Australian Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong

Room 302, 3/F, Lucky Building, 39 Wellington Street, Central, Hong Kong

Tel: (852) 2522 5054 Fax: (852) 2877 0860

austcham@austcham.com.hk www.austcham.com.hk

In 2017 AustCham provided a detailed submission (enclosed) on the benefits of an Australia-Hong

Kong Double Taxation Agreement. The issues discussed in this submission remain significant and

relevant today. There are real and tangible advantages to Australia in terms of greater information and

transparency in entering into a DTA with Hong Kong, including:

• providing complementarity and support to the Australia-Hong Kong Free Trade Agreement

• strengthening investment into Australia, particularly given large infrastructure projects

requiring capital such as green energy and decarbonisation projects

• providing greater access to information in Hong Kong for the ATO

• protecting Australian tax residents temporarily based in Hong Kong, from Australian tax on

their foreign source income (assuming they are allocated to Hong Kong under the tie-breaker

provisions)

• Increasing the attractiveness of Australia for leading global talent, especially international

executives, identified as a solution to addressing Australia’s skills deficit and accelerating

economic growth.

These last two points are particularly critical given the proposed reform of Australia’s individual tax

residency tests and proposed adoption of the Board of Taxation’s recommendations in its 2019 report

1

.

AustCham has actively engaged with Treasury on the proposed recommendations, and I enclose a copy

of our submission to the Australian Government Consultation on Modernising the Individual Tax

Residency Rules (dated 22 September 2023).

Recent developments with the implementation of the OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting

(BEPS) Inclusive Framework also underscore the need for greater certainty a DTA can provide for

Australian businesses in Hong Kong.

If you have any queries about this submission, contact myself on austcham@austcham.com.hk or by

phone +852 6398 6105.

Yours sincerely,

Stefanie Evennett

Chief Executive

Encl.: March 2017, AustCham Hong Kong Submission, Australia - Hong Kong Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement: Securing

economic growth into the future (Confidential)

September 2023, AustCham Hong Kong Submission to Australian Government Consultation on Modernising the Individual Tax Residency

Rules

CC Gareth Williams, Australian Consul-General in Hong Kong

1

The previous Federal Government in the 2021/2022 Federal Budget proposed to consider the recommendations of the Board of Taxation in

reforming Australia’s tax residency rules as contained in its report released in 2019 ‘Reforming Individual Tax Residency Rules – a

model for modernisation’.

The Australian Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong

Room 302, 3/F, Lucky Building, 39 Wellington Street, Central, Hong Kong

Tel: (852) 2522 5054 Fax: (852) 2877 0860

austcham@austcham.com.hk www.austcham.com.hk

Australia - Hong Kong

Comprehensive Double

Taxation Agreement

Securing economic growth into the future

AustCham Hong Kong

March 2017

Contact: Darren Bowdern

AustCham Board of Directors (Treasurer)

& Co-Chair of the Finance, Legal and Tax (FTL) Committee

/ Partner, KPMG in Hong Kong

T: +85 2 2826 7166

E: darren.bowdern@kpmg.com

Document classification: Highly Confidential

Australia - Hong Kong Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement

March 2017

i

Document classification: Highly Confidential

Contents

1 Executive summary 1

2 Background 3

2.1 The challenge of economic growth 3

2.2 The BEPS challenge 3

2.3 Hong Kong’s commitment to expanding its DTA network 4

3 Treaty benefits 6

3.1 Enhance cross-border trade and investment between Australia

and Hong Kong 6

3.2 Gateway to Asian markets 8

3.3 Australia as a major financial centre in Asia 9

3.4 Co-operation on international tax integrity 9

4 Comparison: Singapore DTA 11

5 Perceived loss of revenue 12

6 A more internationally competitive Australia 14

7 The way forward 17

A Hong Kong’s DTA network 18

B Australia’s DTA network 19

Australia - Hong Kong Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement

March 2017

1

Document classification: Highly Confidential

1 Executive summary

Political uncertainties in many parts of the world are impacting the global economic

outlook. At the same time, Governments around the world are also faced with the

challenge of globalisation, which is exacerbating opportunities for tax avoidance.

The idea of a double taxation agreement (“DTA”) between Australia and Hong Kong is

not new, and now is the time for action. This is the time for Australia and Hong Kong to

enter into a DTA to foster increased cross-border trade and investment in the region and

secure economic growth into the future, whilst demonstrating Australia’s and Hong

Kong's commitment to addressing international tax avoidance practices.

Hong Kong is one of Australia’s top 15 partners in terms of trade in goods and services

1

.

Hong Kong is also the 6

th

highest source of investment in Australia; this is followed by

China at the 7

th

position, which also makes a large proportion of its outbound investments

through Hong Kong

2

. Although Australia has an established network of DTAs with its

main trading and investment partners such as China (the DTA does not extend to cover

Hong Kong) and Singapore (which has a similar tax system to Hong Kong), Hong Kong

is a notable absence from Australia’s DTA network.

A DTA between Australia and Hong Kong would provide benefits to both signatories.

Hong Kong has a longstanding economic policy of free enterprise and free trade, and is

strategically located in the heart of Asia and a key financial center in the region.

Geographically and commercially, Hong Kong is an attractive entry point for other

countries looking to do business in the region; in particular, Hong Kong is proven

gateway to China’s high growth markets (which we understand is increasingly important

for Australia).

A DTA between Australia and Hong Kong would foster increased cross-border trade and

investment between the two jurisdictions as well as enhanced access to other parts of

Asia for Australian businesses. Specifically, with regard to Australia’s aspirations to

deliver new sources of growth through innovation

3

, a DTA between Australia and Hong

Kong would support Australian businesses that are seeking to commercialise good ideas

with realising the potential of Asian markets, and in turn, Australia’s shift from the mining

boom to the “ideas booms”. The DTA would provide greater certainty and simplicity for

businesses operating in the region with respect to the taxation of cross-border

investment and transfer of human capital (which is particularly relevant for businesses

built on innovation).

In line with international efforts, the DTA can also be used by Australia and Hong Kong

to jointly respond to the challenge of effective tax administration in today’s global

environment through anti-treaty abuse safeguards, mutual assistance in tax collection,

exchange of tax information and improved dispute resolution, which are common

features in modern DTAs.

1

Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (“DFAT”), Australia’s trade in goods and

services by top 15 partners, 2015-16, http://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/trade-investment/australias-

trade-in-goods-and-services/Pages/australias-trade-in-goods-and-services-2015-16.aspx#partners

2

Australian Government DFAT, Which countries invest in Australia?, 2015,

http://dfat.gov.au/trade/topics/investment/Pages/which-countries-invest-in-australia.aspx

3

Australian Government, National Innovation and Science Agenda: Welcome to the Ideas Boom, 7

December 2015, http://www.innovation.gov.au/page/national-innovation-and-science-agenda-report

Australia - Hong Kong Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement

March 2017

2

Document classification: Highly Confidential

We understand that there have been a number of discussions between the Hong Kong

Financial Services and Treasury Bureau, and the Australian Treasury in the past to

discuss a DTA. The Australian Treasury is, as we understand it, receptive to the idea of

a DTA, subject to an evaluation of the implications of concluding a DTA with Hong Kong.

Specifically, we understand that Australia’s primary concern has related to a potential

loss of revenue as result of entering into a DTA. We note that there should be little impact,

if any, on revenue collection for dividend and interest withholding tax; the only potential

impact is in respect of royalty withholding tax if the DTA were to provide for reduced

royalty withholding tax on royalties paid from Australia to Hong Kong. Given that Hong

Kong has re-affirmed its commitment to expanding its DTA networks

4

, and has

demonstrated willingness to be flexible in treaty negotiations in the past, a DTA between

Australia and Hong Kong could presumably involve a carve-out in respect of the royalty

article, if this is considered necessary.

In any event, it is unlikely that the Australian Taxation Office (“ATO”) would collect any

meaningful amounts of royalty withholding tax on payments to Hong Kong. For Australian

businesses selling technology intensive goods and services into Asian markets, it is more

likely that there would be royalties paid to Australia for the use of intellectual property

developed and located in Australia.

Tax as a “growth friendly” strategy and strengthening cooperation to close the gaps in

international tax rules have never been higher on the agenda for world leaders. By

entering into a DTA with Hong Kong, Australia would be sending the message that it is

looking ahead and committed to supporting the Australian economy’s shift to broader-

based growth by making the most of opportunities offered in Hong Kong and other parts

of the region. This is the time for Australia and Hong Kong to partner up to secure

economic growth into the future.

4

Hong Kong Financial Secretary’s 2017/18 Budget Speech, released on 22 February 2017

Australia - Hong Kong Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement

March 2017

3

Document classification: Highly Confidential

2 Background

2.1 The challenge of economic growth

The World Bank is projecting a growth of 2.7 percent in 2017 for the global economy

after a post-crisis low last year

5

. The shifting political landscape in many parts of the

world – for example, the United Kingdom’s (“UK”) decision to leave the European Union

(“Brexit”), the United States (“US”) Presidential Election in 2016 and political uncertainty

ahead of crucial elections in the eurozone

6

– is impacting the global economic outlook.

A need for action to manage the associated uncertainties is high on the agenda for world

leaders.

In Australia, the economy continues to transition from the investment phase to the

production phase of the mining boom and the challenge is achieving broader-based

growth.

7

As the International Monetary Fund (“IMF”) noted in its annual assessment of

the Australian economy, although economic growth in Australia has been relatively

robust despite the unwinding of the mining boom, “Australia has not been immune to the

new mediocre”

8

. We understand that the Australian Federal Government is focused on

securing Australia’s economic growth in light of the significant risks and uncertainties

ahead such as weaker than expected domestic consumption and rise of protectionist

measures in G20 economies

9

. Indeed, the IMF has endorsed the Australian

Government’s reform agenda given the focus on strengthening competition and fostering

innovation, and Australia’s commitment to “an open economy in trade, foreign investment

and immigration”

10

.

2.2 The BEPS challenge

At the same time, there have been significant changes in the international tax landscape

in recent years to address the risk of tax base erosion and profit shifting by multinationals.

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the G20 and OECD have partnered to

establish a modern international tax framework that is focused on:

— Ensuring that profits are taxed where the value is created; and

— Tax transparency as a means of enabling improved accountability and cooperation

between taxpayers and tax administrations.

5

World Bank Group Flagship Report, Global Economic Prospects: Weak Investment in Uncertain Times,

January 2017, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/25823/9781464810169.pdf

6

The Netherland’s General Election was held on 15 March 2017 and is the first in series of elections

across Europe this year, which includes France’s Presidential Election (first round on 23 April 2017,

second round on 7 May 2017) and Germany’s Federal Election on 22 October 2017

7

The Australian Federal Government’s Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2016-17, December 2016,

http://www.budget.gov.au/2016-17/content/myefo/html/

8

International Monetary Fund (“IMF”), IMF Executive Board Concludes 2016 Article IV Consultation with

Australia, 9 February 2017, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2017/02/09/PR1741-Australia-IMF-

Executive-Board-Concludes-2016-Article-IV-Consultation

9

OECD/ World Trade Organisation (“WTO”)/ United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

(“UNCTAD”), Reports on G20 Trade and Investment Measures (Mid May to Mid-October 2016), 10

November 2016, https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news16_e/g20_joint_summary_november16_e.pdf

10

Refer Note 7

Australia - Hong Kong Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement

March 2017

4

Document classification: Highly Confidential

Since the G20/OECD first embarked on this project (referred to as the Base Erosion and

Profit Shifting (“BEPS”) Project), more than 60 jurisdictions have been involved in

delivering the 15 Action Plans under the BEPS Project (released in November 2015)

11

.

There are now more than 90 jurisdictions (including Australia and Hong Kong) who are

working together to set standards for the implementation of the BEPS Action Plans in

their domestic tax laws

12

. Specifically, these jurisdictions have committed to four

minimum standards:

— Countering harmful tax practices more effectively;

— Preventing treaty abuse;

— Imposing country-by-country reporting requirements; and

— Improving the cross-border dispute resolution regime

13

.

For instance, as part of its commitment to implement a model that meets international

standards, Hong Kong has recently announced the introduction of specific transfer

pricing rules that are aimed at ensuring that taxpayers earn an arm’s length profit for the

activities they are performing, and which include mandatory transfer pricing

documentation requirements

14

.

In connection with the BEPS Project, Australia and Hong Kong, together with more than

other 100 jurisdictions, have also participated in developing the Multilateral Convention

to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent Base Erosion and Profit Shifting

(“the Multilateral Instrument”) (released on 31 December 2016 with signature by the

relevant countries planned for June 2017)

15

. The Multilateral Instrument implements

standards for countering treaty abuse, improve dispute resolution mechanisms and

strengthen the tax treaty related measures developed under the BEPS Project.

2.3 Hong Kong’s commitment to expanding its DTA network

Hong Kong is the leading financial services centre in Asia, as well as the preferred

regional or head office jurisdiction for many multinational and Asian corporations. Hong

Kong is looking to further capitalise on its status as a head office and financial services

centre, and to promote cross-border trade and investment between China and the rest

of the world. Hong Kong’s proximity to China and other parts of Asia, and its international

business environment, makes it a preferred jurisdiction for investors to establish

business operations and to hold their investments in Asia. In support of this, Hong Kong

has been actively seeking to expand its DTA network. DTAs have already been signed

with China, the UK, France, Switzerland, Malaysia and Indonesia (37 jurisdictions in total

11

OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, 2015 Final Reports, http://www.oecd.org/ctp/beps-

2015-final-reports.htm

12

OECD Inclusive Framework on BEPS Composition as at 5 January 2017,

https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/inclusive-framework-on-beps-composition.pdf

13

OECD, BEPS: About BEPS and the inclusive framework, http://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/beps-about.htm

14

On 26 October 2016, the Hong Kong Government issued a consultation paper on a range of measures

including a proposal to introduce specific transfer pricing rules for Hong Kong. Draft legislation is expected

to be introduced by mid-2017

15

OECD’s Information Brochure on the Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related

Measures to Prevent Base Erosion and Profit Shifting, http://www.oecd.org/tax/treaties/multilateral-

instrument-BEPS-tax-treaty-information-brochure.pdf

Australia - Hong Kong Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement

March 2017

5

Document classification: Highly Confidential

as of 28 February 2017).

16

Hong Kong has also signed a DTA with New Zealand and

Canada, and is currently negotiating a DTA with Germany, jurisdictions with similar

taxation regimes to that of Australia.

More recently, Hong Kong has signed DTAs with Russia (18 January 2016), Latvia (13

April 2016) and Belarus (16 January 2017) and Pakistan (17 February 2017), major

developing economies along the “One Belt One Road”. Hong Kong is continuing its

efforts to expand its network of DTAs with other trading and investment partners. In

addition to current negotiations with Australia, Hong Kong is also in negotiations with a

further 14 jurisdictions (including India and Germany).

16

Refer Appendix A: Hong Kong’s DTA network

Australia - Hong Kong Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement

March 2017

6

Document classification: Highly Confidential

3 Treaty benefits

Australia is currently a party to 44 DTAs (as at 28 February 2017), including the revised

DTA with Germany that was signed on 12 November 2015.

17

While Australia has treaties

with many trading partners (including some neighbouring Asian jurisdictions), most of

them are relatively old and the existing DTA between Australia and China does not

extend to cover Hong Kong.

There is an opportunity here for Australia and Hong Kong to enter into a DTA to minimise

barriers to key drivers of economic growth such as investment, innovation and

entrepreneurship. A DTA between Australia and Hong Kong helps ensure that Australia

is in a competitive position for trade and investment with Hong Kong as well as other

parts of Asia, which would provide benefits to both jurisdictions. The mutual benefit of

increased cross-border trade and investment supports innovation, job creation and future

economic growth for Australia and Hong Kong.

3.1 Enhance cross-border trade and investment between Australia

and Hong Kong

Australia and Hong Kong have a longstanding and significant trading relationship. Hong

Kong is Australia’s 12

th

largest two-way trading partner (2015-16)

18

, including being

Australia’s 6

th

largest destination for merchandise exports (A$8.8 billion) and 7

th

largest

destination for service exports (A$2.3 billion)

19

.

Hong Kong is also the 6

th

largest source of foreign investment for Australia (A$85.4 billion

in 2015). This outranks direct investment from China into Australia (A$74.5 billion in

2015)

20

, noting that many Chinese enterprises prefer to manage their outbound

investments through Hong Kong. Hong Kong’s investment in Australia ranges from

infrastructure and telecommunications to banking, property development, transport,

hospitality and agriculture

21

.

Importantly, there is room for growth. Based on Australia’s International Business Survey

2016 (“AIBS 2016”), which captures responses from more than 900 Australian

businesses undertaking international activities, Hong Kong is expected to be a key new

market for the “Information, Communications and Technology” (“ICT”) (ranked 7th) and

“professional, scientific and technical services” (ranked 8th) sector, in terms of additional

revenue expected over the next two years. This suggests that Australian business are

seeing opportunities for increased technology intensive goods and service exports to

Hong Kong. This is also consistent with a recent report on “Australia

’

s jobs future: The

rise of Asia and the services opportunity”

22

, which noted that service exports from

Australia to Asia are underperforming relative to Australia’s traditional partners and

17

Refer Appendix B: Australia’s DTA network

18

Refer Note 1

19

Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (“DFAT”), Trade and economic

factsheet for Hong Kong, December 2016, http://dfat.gov.au/trade/resources/Documents/hong.pdf

20

Refer Note 2

21

Hong Kong Financial Secretary, Australian Consulate-General Australia Day Reception Address on 24

January 2017, http://www.news.gov.hk/en/record/html/2017/01/20170124_204510.shtml

22

ANZ/ PwC/ Asialink Business Services Report, Australia’s jobs future: the rise of Asia and the services

opportunity”, April 2015, https://www.pwc.com.au/asia-practice/assets/anz-pwc-asialink-apr15.pdf

Australia - Hong Kong Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement

March 2017

7

Document classification: Highly Confidential

concluded that by employing the right strategies, services can become Australia’s

number one export to Asia in terms of total value added, creating jobs in the process

23

.

At the same time, innovation and technology development is high on the Hong Kong

Government’s policy agenda, and Hong Kong’s Financial Secretary has expressed a

desire to partner with Australia in this area

24

.

Against this backdrop, a DTA between Australia and Hong Kong would foster bilateral

economic activity, and in particular, the commercialisation of technology intensive goods

and services in Asia by Australian businesses.

Based on a study conducted by the Australian Government’s Productivity Commission,

one of the barriers to growth in Australian service exports relates to investment in

Australian service providers

25

. Australia has always relied on foreign investment to drive

economic growth (and with it, growth in employment)

26

. However, tax laws in Australia

are often seen as very complex and can change suddenly. As tax certainty and simplicity

are some of the factors to consider in deciding whether to invest in Australia or

elsewhere, a DTA between Australia and Hong Kong would support increased

investment from Hong Kong into Australia by specifying the maximum rates of

withholding taxes that can be applied to dividends, interest and/or royalties. This allows

investors to make investment decisions with greater confidence and reduces compliance

costs for investors by making it easier to determine potential returns on investments.

Barriers to attracting skilled employees and impediments to the movement of services

have also been identified in the Productivity Commission’s study as barriers to growth in

Australian service exports. These could have a substantial effect on the supply of service

exports by increasing the ongoing costs of export operations and/or limiting the supply

of exports

27

. The services sector is particularly reliant on the availability of skilled

employees and in the case of service exports, entails a greater degree of cross-border

movement of employees than the export of goods. A DTA between Australia and Hong

Kong would reduce potential impediments in these areas by supporting the movement

of employees between these jurisdictions. For employees engaged in certain short-term

income-earning activities in Hong Kong, it could reduce compliance costs and provide

cash flow advantages by eliminating the need to pay tax in that jurisdiction (i.e. Hong

Kong) and then claim that tax against the tax liability in their home jurisdiction (i.e.

Australia). It would also support Australian businesses with the exchange of ideas for

innovation, developing an “Asia capable” workforce and competing on an international

level by leveraging from the experience of those in Hong Kong.

23

Commissioned by the Export Council of Australia (“ECA”) with the support of Austrade and Export

Finance and Insurance Corporation (“Efic”), http://www.austrade.gov.au/ArticleDocuments/1358/AIBS-

2016-full-report.pdf.aspx

24

Refer Note 20

25

Australian Government, Productivity Commission Research Report on Barriers to Growth in Service

Export, November 2015,

http://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/service-exports/report/service-

exports.pdf

26

Australian Government DFAT, Australia and Foreign Investment,

http://dfat.gov.au/trade/topics/investment/Pages/frequently-asked-questions.aspx

27

Refer Note 24

Australia - Hong Kong Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement

March 2017

8

Document classification: Highly Confidential

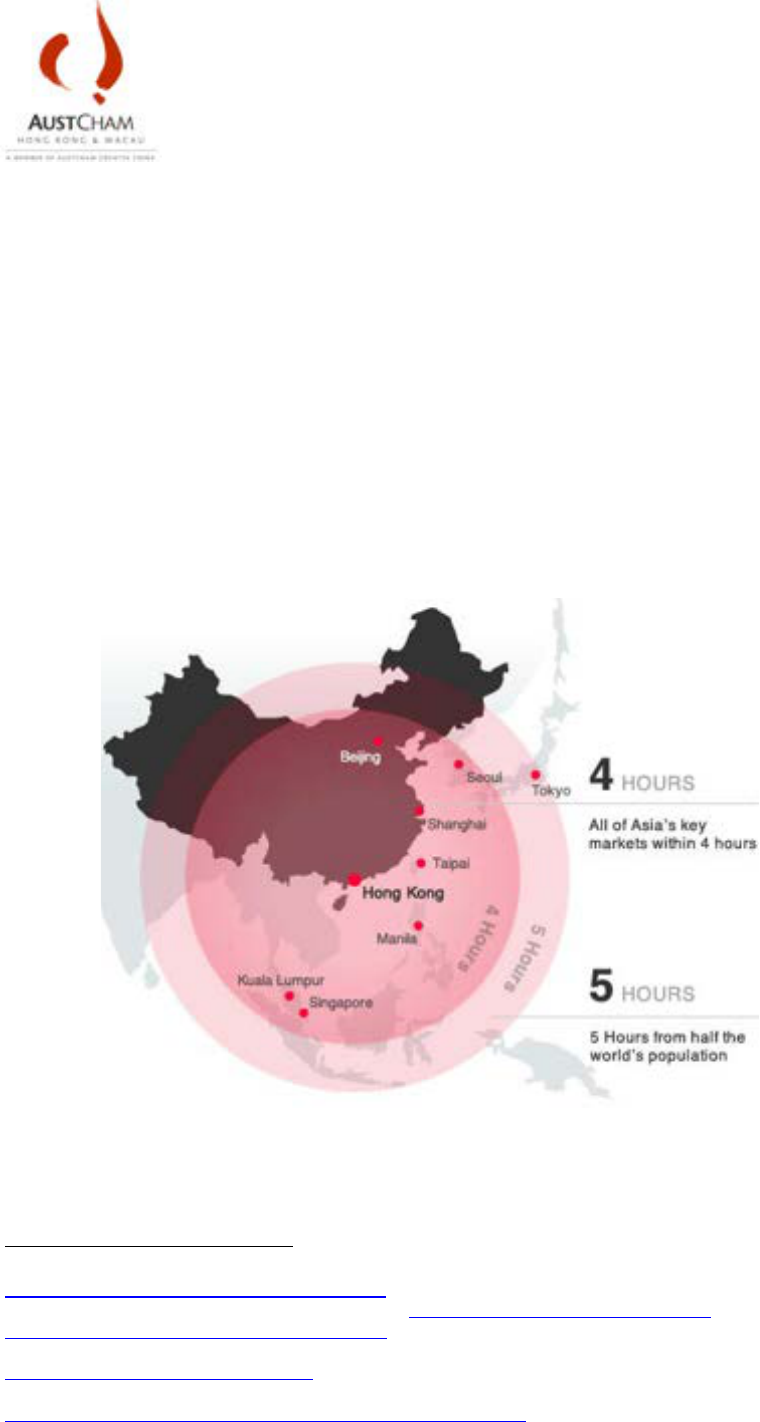

3.2 Gateway to Asian markets

For Australian businesses looking to do business in Asia, Hong Kong is an attractive

entry point. Hong Kong is the top ranking jurisdiction on the Heritage Foundation’s Index

of Economic Freedom, which takes into account 12 quantitative and qualitative factors

(including government integrity, fiscal health, business freedom, trade freedom and

investment freedom), and has held this position for the last 22 years

28

. Hong Kong also

ranks 4th out of 190 economies on the World Bank’s “ease of doing business” rankings

29

.

Geographically, Hong Kong is located at the heart of Asia. Key Asian cities such as

Beijing, Shanghai, Singapore, Taipei, Manila and Kuala Lumpur are in the same time

zone as Hong Kong; Bangkok, Jakarta, Seoul and Tokyo are all within an hour’s

difference. Hong Kong’s success as a gateway to other Asian markets is underpinned

by peerless transport connections in the region. All of Asia’s key markets are less than

four hours’ flight time from Hong Kong; half of the world’s population is within five hours’

flight time from Hong Kong

30

.

Figure 3.1 Hong Kong’s strategic location

31

28

Heritage Foundation, 2017 Index of Economic Freedom,

http://www.heritage.org/index/country/hongkong;

The Government of the Hong Kong Special

Administrative Region InvestHK, Why Hong Kong, http://www.investhk.gov.hk/why-hong-

kong/international-transparent-and-efficient.html (last modified on 25 October 2016)

29

The World Bank, “Ease of Doing Business” Economy Rankings (2017),

http://www.doingbusiness.org/rankings

30

The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region InvestHK, Why Hong Kong,

http://www.investhk.gov.hk/why-hong-kong/strategic-location.html

(last modified on 25 October 2016)

31

Source: refer Note 29

Australia - Hong Kong Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement

March 2017

9

Document classification: Highly Confidential

In particular, Hong Kong is a proven gateway into the Chinese high growth market and

has been used as an entry point by Australian exporters seeking to enter the Chinese

market. China remains a mainstay in supporting the global economic growth. The World

Bank is projecting a growth of 6.5 percent in 2017 for China and a medium-high growth

looking further ahead

32

. The growth in China and other parts of Asia represents an

opportunity for Australian businesses looking to increase market share (in particular,

through increased service exports to the region). Australian companies looking to do

business in Asia would benefit from the conclusion of a DTA between Australia and Hong

Kong. By fostering increased trade and investment between Australia and Hong Kong,

a DTA between the two jurisdictions is also supporting enhanced access to Asian

markets (through Hong Kong) for Australian businesses.

3.3 Australia as a major financial centre in Asia

We understand that Australia is seeking to establish closer economic ties with Asia and

to further its status as a major financial centre in the region. In this area, Hong Kong is

widely seen as one of the leading international and regional financial centres in Asia, and

the head or regional office location to some of Asia's largest corporate groups and many

multinational corporations.

By entering into a DTA with Hong Kong, Australia would be taking a step towards

fostering closer economic ties with Asia because of the role that Hong Kong has in

international financial and capital markets, and achieving improved interoperability

between Australia and Hong Kong as two of the key financial centres in the region.

Australia and Hong Kong have already sought to foster closer collaboration on renminbi

(“RMB”) trade settlement, the development of RMB-denominated products and closer

RMB banking and financial links, with regard to the increasing importance of the RMB

as a trade and investment currency in the region. Hong Kong was the first offshore

market to launch the RMB business in 2004, and remains the largest offshore RMB

hub

33

. In 2012, Australia and Hong Kong established a high-level dialogue between

respective senior business leaders to identify new opportunities arising from RMB use in

trade and investment in the region. The first Australia-Hong Kong RMB Trade and

Investment Dialogue was held in Sydney (April 2013); the second in Hong Kong (May

2014); and the third was again held in Sydney (July 2015). Based on SWIFT’s latest

RMB tracker (February 2017), Australia currently ranks as the 8

th

largest offshore RMB

clearing centre

34

.

3.4 Co-operation on international tax integrity

An important feature of the Hong Kong DTA is the inclusion of a standard OECD

information exchange article, which will give Australia the ability to request and exchange

32

Refer Note 5

33

Hong Kong Monetary Authority (“HKMA”), Hong Kong: The Global Offshore Renminbi Business Hub,

January 2016, http://www.hkma.gov.hk/media/eng/doc/key-functions/monetary-stability/rmb-business-in-

hong-kong/hkma-rmb-booklet.pdf

34

SWIFT, RMB Tracker: Monthly reporting and statistics on renminbi (“RMB”) progress towards becoming

an international currency, February 2017, retrieved from https://www.swift.com/our-solutions/compliance-

and-shared-services/business-intelligence/renminbi/rmb-tracker/document-centre

Australia - Hong Kong Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement

March 2017

10

Document classification: Highly Confidential

information with the tax authorities in Hong Kong. Hong Kong, as a leading financial

centre, has now adopted the Common Reporting Standard (“CRS”). Under the CRS

framework, financial institutions in Hong Kong are required to collect and report the

financial account information relating to tax residents of “reportable jurisdictions” to the

Hong Kong Inland Revenue Department (“IRD”), commencing 2018 with respect to 2017

account information. Subject to entering into the relevant bilateral agreements, Hong

Kong can then also exchange the CRS information automatically with other jurisdictions.

Hong Kong’s list of reportable jurisdictions currently comprise Japan and the UK, and

there are plans to add a further 72 jurisdictions to this list (which includes Australia) with

effective from 1 July 2017

35

. For these new reportable jurisdictions, the IRD can only

exchange the CRS information with the other relevant jurisdiction after it has signed a

Competent Authority Agreement with that jurisdiction.

A DTA between Australia and Hong Kong in these circumstances would therefore enable

tax officials to detect and prevent tax avoidance and evasion in both jurisdictions.

Specifically, a DTA would enable Hong Kong to conclude a Competent Authority

Agreement with Australia, which will allow it to exchange information on an automatic

basis with Australia.

As signatories to the Inclusive Framework on BEPS and the Multilateral Instrument

(which implements standards for countering treaty abuse, improving dispute resolution

mechanisms and strengthening the tax treaty related measures developed under the

BEPS Project), a DTA between Australia and Hong Kong would provide the two

jurisdictions with the opportunity to coordinate their approach and to give effect to the

G20/OECD’s recommendations for addressing the risk of tax base erosion and profit

shifting by multinationals using artificial or contrived arrangements. For example,

features between the DTA between Australia and Hong Kong could include provisions

for revenue agencies in the two jurisdictions to assist each other in the collection of any

outstanding tax debts, and to clarify the circumstances in which a taxable “permanent

establishment” will arise.

A DTA between Australia and Hong Kong would demonstrate that both jurisdictions

remain committed to maintaining a fair tax environment and aligning with international

standards on tax modernisation.

35

Hong Kong Legislative Council Panel on Financial Affairs, Update on Implementation of Automatic

Exchange of Financial Information in Tax Matters (“AEOI”), LC Paper No. CB(1)660/16-17(09) for

discussion on 16 March 2017, http://www.legco.gov.hk/yr16-17/english/panels/fa/papers/fa20170316cb1-

660-9-e.pdf

Australia - Hong Kong Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement

March 2017

11

Document classification: Highly Confidential

4 Comparison: Singapore DTA

It is relevant to note that Australia concluded a DTA with Singapore in 1969, a jurisdiction

with a similar taxation system to Hong Kong. Both Singapore and Hong Kong have a

“territorial” system of taxation such that it is only income sourced in that country which is

subject to tax there.

36

Further, Singapore does not impose tax on capital gains or

dividends. Singapore also has a comparable corporate tax rate to Hong Kong, being

17%. In addition, Singaporean withholding tax rates for recipients resident in a non-tax

treaty jurisdiction are 10% for royalties, and 15% for interest.

Under the Australian DTA with Singapore, the withholding tax rates are;

— 15% for interest; and

— 10% for royalties.

As noted above, Singapore does not impose withholding tax on dividends.

Similar to a DTA between Hong Kong and Australia, under the Singapore treaty,

Singapore has not forgone any withholding tax as result of entering in to the DTA. Yet,

this is as we understand, is one of the key reservations that Australia may have when

considering a DTA with Hong Kong. The Australia – Singapore DTA may therefore serve

as a useful reference point in negotiations between Hong Kong and Australia. As

Australia has had such a long standing DTA with Singapore, Australia should be able to

reach an agreement on a DTA with Hong Kong, which has a similar tax system to

Singapore.

36

However, Singapore also taxes companies on foreign source income remitted into Singapore, which has

been taxed at a rate less than 15%

Australia - Hong Kong Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement

March 2017

12

Document classification: Highly Confidential

5 Perceived loss of revenue

As outlined above, a DTA between Australia and Hong Kong would bring clear benefits

to both jurisdictions. However, for Australia, we understand that there had been concerns

in the past on the potential loss of revenue that may occur under a DTA.

Ordinarily, both parties entering into a DTA would make reciprocal withholding tax rate

reductions. However, Hong Kong generally does not levy withholding taxes (it does

impose a low rate of withholding tax on royalties, however this is likely to be the same

rate specified in a DTA) and therefore, Hong Kong should not actually forego any

withholding tax.

By way of reference, Australian withholding tax rates for recipients resident in a non-tax

treaty jurisdiction are;

— 30% for unfranked dividends;

— 30% for royalties; and

— 10% for interest.

We understand that the principal concern in Australia if it were to enter into a DTA with

Hong Kong, would be the impact this may have on revenue collection. However,

expectations of a loss of revenue may be more illusory than real. In an article that

discussed the impact that a DTA with Hong Kong would have for Australia

37

, in the

context of employment income and business profits, the conclusion was that a DTA

should only have a minimal impact from a revenue perspective. More particularly, the

article also concluded that an agreement would provide taxpayers from both jurisdictions

with increased certainty about their exposure to tax in the jurisdictions.

One of the main benefits of a DTA is that the reduction in withholding taxes that apply to

dividends and interest. However, a DTA between Hong Kong and Australia is likely to

have little impact in this regard. In the case of dividends, the impact is likely to be

negligible because only unfranked dividends are subject to withholding tax in Australia.

An unfranked dividend refers to, broadly, dividends paid by companies out of profits

which were not subject to Australian tax. Accordingly, any reduction in the dividend

withholding tax rate is likely to have immaterial impact on the current revenue collection

in Australia in respect of dividends paid to Hong Kong residents.

In respect of interest, Australia’s DTAs typically do not offer a lower withholding tax rate.

As such, there would be no impact on the revenue collection for Australia in respect of

interest withholding tax.

However, the article acknowledged that a DTA was likely to negatively impact the

withholding tax revenues collected by Australia from royalties paid to residents of Hong

Kong. Ordinarily, we would expect the royalty withholding tax in a DTA to be reduced to

10% (resulting in a reduction of 20% for Australia). It is acknowledged that the most

significant impact that the signing of a DTA would have is on taxation of royalties by

Australia. However, international corporations with potential royalty cross-border

payments are likely to structure contract terms to ensure the payments are made in the

most tax efficient manner. Although we have not sighted any applicable data, we would

37

Nolan Cormac Sharkey and Kathrin Bain, eJournal of Tax Research Volume 9 Number 3, December

2011, An Australia-Hong Kong double tax agreement: Assessing the costs and benefits

Australia - Hong Kong Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement

March 2017

13

Document classification: Highly Confidential

not expect significant royalty payments being made from Australia to Hong Kong.

Accordingly, we would question the significance of a reduction on royalty withholding tax

on revenue collection in Australia. In any event, if this were a concern to the Australian

Government, this issue could be dealt with in the DTA. That is, the DTA would be agreed

with no reduction in withholding taxes for royalties.

It is important to note however, that to the extent Australia has concerns on the possible

loss of revenue from any part of a DTA, the Hong Kong Government would, we believe,

be prepared to be flexible and address any such concerns in the course of the DTA

negotiations. As noted, royalty withholding tax is an article Hong Kong could carve out

of a potential DTA for the purposes of negotiations with Australia.

Further, Hong Kong’s existing DTA network covers most of Europe and Asia (including

many advanced economies such as the UK, Canada, Japan and France). We

understand that Hong Kong’s existing treaty partners have benefited from entering into

a DTA with Hong Kong in that the DTA has made treaty partner jurisdictions a more

attractive destination for investment from Hong Kong (including investment from Chinese

investors that structure their investments through Hong Kong) and have supported their

growing presence in Asia, without significant loss in revenue from entering into the DTA.

For comparison, we note that New Zealand (which has a comparative tax system to

Australia) signed a DTA with Hong Kong on 1 December 2010. The revenue cost to

New Zealand as a result of the reduction in withholding rates afforded in the DTA was

expected to be relatively small, at approximately NZ$0.5 million per year.

38

In this case,

the New Zealand Parliament was satisfied that the advantages of the entering a DTA

with Hong Kong outweigh the potential disadvantages. From an Australian perspective,

a DTA would almost certainly result in increased trade and investment flows between

Australia and Hong Kong, which should, in our opinion, outweigh any potential loss of

revenue from, for example, reduced withholding taxes on profit flows offshore. Should

this issue continue to be a concern of Australia, Australia should consider engaging in a

similar exercise in attempt to quantify, if any, the loss of revenue as a result of entering

into a DTA with Hong Kong.

38

Parliament of New Zealand, Dr Craig Latham, National Interest Analysis: Double Tax Agreement with

the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China

Australia - Hong Kong Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement

March 2017

14

Document classification: Highly Confidential

6 A more internationally competitive Australia

According to the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index (2016-17)

(“Index”), which assesses the competitiveness of 138 economies in a global context,

Australia ranks 22

nd

overall

39

. In comparison, Hong Kong has ranked in the top 10 for the

fifth consecutive year

40

. The Index highlights that “tax rates” and “tax regulations” are

two of the top five most problematic factors for doing business in Australia.

This is consistent with the Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (“RBA”) recent

comments that there is a need to ensure that Australia’s tax system is internationally

competitive given the impact on Australia’s attractiveness as a destination for trade and

investment, which plays a critical role in Australia’s future prosperity

41

. The RBA

Governor noted that from a government revenue perspective, this may be supported

through reducing spending or rebuilding revenue in other areas.

We understand that the Australian Government recognises the risk of Australia falling

further behind international competitors and the role of reducing the tax burden on

Australian employers in managing this challenge

42

. In particular, the Government has

responded with a fully funded “Ten Year Enterprise Tax Plan”, which is aimed at reducing

the Australian corporate tax rate to help Australian businesses compete, noting that 15

years ago, Australia enjoyed the 9

th

lowest corporate tax rate amongst advanced

economies whereas today, Australia (corporate tax rate of 30%) has the 6

th

highest

corporate tax rate amongst 35 OECD countries

43

.

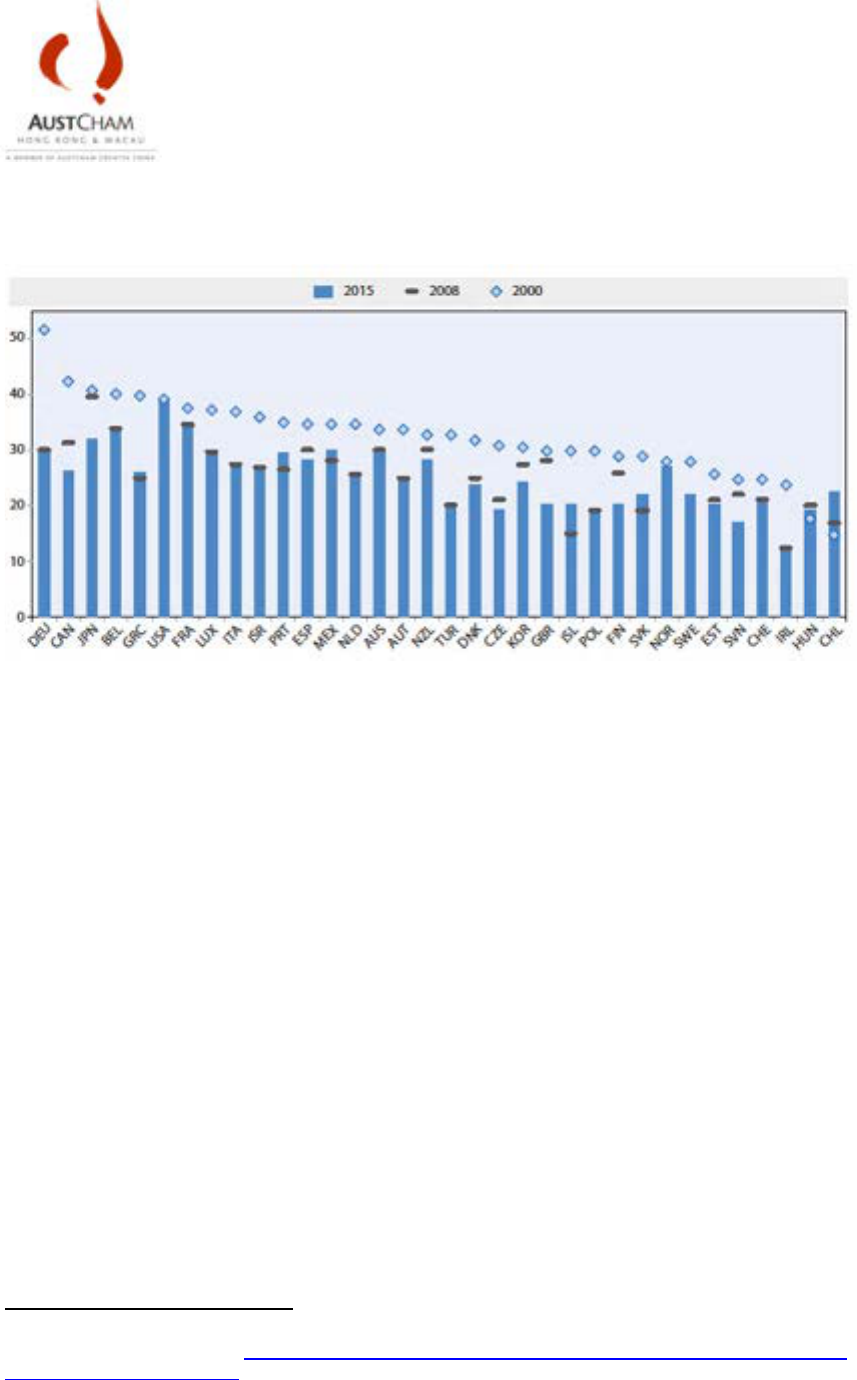

According to the OECD’s report on tax developments across OECD countries, the

average corporate tax rate declined from 32% in 2000 to 25% in 2015 with five OECD

countries having implemented rate reductions in that year

44

. Looking ahead, many

countries such as the US, UK, France, Japan and Italy announced plans to lower their

corporate tax rates. In particular, the UK has announced a reduction of its headline

corporate tax rate down to 17% by 2020 to provide “the right conditions for business

investment and growth”, following government analysis showing that the reduction in tax

rates could increase gross domestic product (“GDP”) by between 0.6% and 1.1% longer

term

45

. In the US, which has one of the highest statutory corporate tax rates in the world

(35%), President Trump has indicated in his first joint address to Congress on 28

February 2017 that his economic team “is developing historic tax reform that will reduce

39

World Economic Forum, Global Competitiveness Index (2016-17), Australia,

http://sjm.ministers.treasury.gov.au/media-release/011-2017/

40

World Economic Forum, Global Competitiveness Index (2016-17), Hong Kong,

http://reports.weforum.org/global-competitiveness-index/country-profiles/#economy=HKG

41

Reserve Bank of Australia (“RBA”) Governor Philip Lowe’s Speech at the A50 Australian Economic

Forum Dinner on 9 February 2017, https://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2017/sp-gov-2017-02-09.html

42

The Honourable Scott Morrison MP, Treasurer of the Commonwealth of Australia, Media Release,

“Labor has run out of excuses on business tax cuts as RBA governor exposes their threat to jobs”, 10

February 2017, http://sjm.ministers.treasury.gov.au/media-release/011-2017/

43

The Honourable Scott Morrison MP, Treasurer of the Commonwealth of Australia, Media Release,

“Turnbull Government’s Enterprise Tax Plan to drive investment, jobs and wages”, 1 February 2017,

http://sjm.ministers.treasury.gov.au/media-release/005-2017/

44

OECD, Tax Policy Reforms in the OECD 2016, 22 September 2016, http://www.oecd-

ilibrary.org/taxation/tax-policy-reform-in-the-oecd-2016_9789264260399-en

45

HM Revenue & Customs, Policy Paper: Corporate Tax to 17% in 2020, 16 March 2016,

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/corporation-tax-to-17-in-2020/corporation-tax-to-17-in-2020

Australia - Hong Kong Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement

March 2017

15

Document classification: Highly Confidential

the tax rate on our companies so that they can compete and thrive anywhere and with

anyone. It will be a big, big cut”

46

.

Figure 6.1 Downward trend in corporate tax rates

47

The OECD predicts that the downward trend on corporate tax rates is accelerating as

the focus of tax reforms have shifted towards the pursuit of economic growth by reducing

taxes on labour and corporate income

48

.

In light of these trends in other parts of the world, a DTA between Australia and Hong

Kong would help Australia to remain internationally competitive. Currently, more than

500 Australian businesses are headquartered in Hong Kong, and more than 1,000

Australian businesses have representative offices in Hong Kong

49

. As outlined above,

there is also an opportunity for Australian businesses that do not currently have a

presence in Hong Kong to expand into the region to realise the potential of Asian

markets.

Businesses have always wanted the right people in the right places. However, the level

of investment required to implement international assignments are often an issue from a

planning, cost and time perspective.

International short term assignments can lead to additional tax and administrative costs

on employees and employers. A DTA between Australia and Hong Kong facilitates the

mobilisation of employees between these jurisdictions by removing tax related

impediments for short term assignments. In particular, the DTA can provide a level of

protection for both employees operating cross-border under short term assignments and

the relevant employers by providing greater certainty and simplicity when it comes to

assessing and complying with the tax requirements on both sides (e.g. whether the

46

The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, Remarks by President Trump in Joint Address to

Congress, 28 February 2017,

https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/02/28/remarks-president-

trump-joint-address-congress

47

Source: refer Note 43

48

Refer Note 43

49

Refer Note 20

Australia - Hong Kong Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement

March 2017

16

Document classification: Highly Confidential

employee is satisfying their tax obligations in the relevant jurisdictions and whether

employee movements are triggering any tax reporting and withholding obligations for the

business. In the absence of a DTA, there could be potential cash flow issues for

employees, an additional layer of cost for employers and employees as well as increased

administrative burden for both employees and employers

50

.

By removing impediments to short term assignments, a DTA between Australia and

Hong Kong supports Australian businesses with achieving overall business goals and

objectives such as expansion into new markets (e.g. China’s high growth markets),

regional business management and global leadership development. For example,

Australian businesses with regional operations may require the skills and experience of

a particular Australian based employee in their Hong Kong office (e.g. an employee with

a regional Asia-Pacific role); Australian business with Hong Kong headquarters may

require a particular Hong Kong based employee (e.g. senior level management from the

Hong Kong head office) in Australia to develop particular set of skills for staff in Australia

(i.e. build the talent pool) or to grow a part of the business in Australia. The mobilisation

of employees between Australia and Hong Kong could also be desirous for designated

projects that require closer collaboration and connectivity between participating

employees in Australia and Hong Kong.

50

Individuals operating between Australia and Hong Kong may be subject to tax on the same employment

income under the tax rules of both Australia and Hong Kong. Although it is possible to avoid double taxation

by the individual claiming credits in their individual income tax return for the tax already paid in the other

jurisdiction (‘foreign tax credits”) as an offset against the tax liability in their home jurisdiction, the mechanism

for claiming foreign tax credits can result in cash flow issues for the individual. For Hong Kong employees

operating in Australia, there could also be an additional layer of tax as the applicable tax rate in Australia is

higher than in Hong Kong. In practice, employers may seek to manage this issue by providing a loan to the

relevant individual(s). However, this results in additional costs for employers seeking to use such short term

assignments to maintain competitiveness and/or expand into new markets. Further, in the absence of a DTA

between Australia and Hong Kong, there could also be employer reporting obligations in both jurisdictions

in respect of the salary and benefits paid to the individual operating cross-border.

Australia - Hong Kong Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement

March 2017

17

Document classification: Highly Confidential

7 The way forward

We understand that the general consensus in the business community in Australia is in

favour of Hong Kong and Australia concluding a DTA.

Hong Kong and Australia have extensive business and social ties, and a DTA would

further promote cross-border trade, investment and employment between the two

jurisdictions.

It is important to raise the debate on the potential advantages to Australia from

concluding a DTA with Hong Kong, rather than focusing on any possible loss of revenue

from a reduction in Australian withholding tax rates. As outlined above, the potential

advantages from entering into a DTA, for both jurisdictions, far outweigh any potential

disadvantages (if any).

Against a backdrop of global political and economic uncertainties, and given what is at

stake as the world becomes smaller and the Australian economy continues to transition

away from the mining boom, now is the time to prioritise entering into a DTA between

Australia and Hong Kong to foster increased cross-border trade and investment in the

region and secure economic growth into the future.

Improve

international

competitiveness

Boost

innovation

Secure

economic

growth

Attract increased investment into Australia

from Hong Kong (including Chinese

investment via Hong Kong)

Enhance access to potential growth markets in

Asia through Hong Kong for Australian

businesses to increase market share

Facilitate exchange of employees to develop

skills and talent pool, and achieve business

growth

Further Australia’s and Hong Kong’s status as

two of the key regional financial centres in the

region

Coordination and cooperation between

Australia and Hong Kong to address

international tax avoidance practices

No loss of revenue expected

Australia - Hong Kong Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement

March 2017

18

Document classification: Highly Confidential

A Hong Kong’s DTA network

The table below lists those jurisdictions (37) that, as of 28 February 2017, have signed

a comprehensive tax treaty with Hong Kong.

Austria Japan Portugal

Belarus Jersey Qatar

Belgium Korea Romania

Brunei Kuwait Russia

Canada Latvia South Africa

China (Mainland) Liechtenstein Spain

Czech Republic Luxembourg Switzerland

France Malaysia Thailand

Guernsey Malta United Arab Emirates

Hungary Mexico United Kingdom

Indonesia Netherlands Vietnam

Ireland New Zealand

Italy Pakistan

The table below lists those jurisdictions that, as of 28 February 2017, Hong Kong is

engaged in negotiations with for a comprehensive tax treaty.

Bahrain India Nigeria

Bangladesh Israel Pakistan

Cyprus Macao SAR Saudi Arabia

Finland Macedonia Turkey

Germany Mauritius

Australia - Hong Kong Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement

March 2017

19

Document classification: Highly Confidential

B Australia’s DTA network

The table below lists those jurisdictions (44) that, as of 28 February 2017, have a

comprehensive tax treaty with Australia. This includes 25 jurisdictions that have

separately signed a comprehensive tax treaty with Hong Kong.

Argentina Ireland Singapore

Austria Italy Slovakia

Belgium Japan South Africa

Canada Kiribati South Korea

Chile Malaysia Spain

China (Mainland) Malta Sri Lanka

Czech Republic Mexico Sweden

Denmark Netherlands Switzerland

Fiji New Zealand Taipei

Finland Norway Thailand

France Papua New Guinea Turkey

Germany Philippines United Kingdom

Hungary Poland United States

India Romania Vietnam

Indonesia Russia

The Australian Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong

Room 301-2, 3/F, Lucky Building, 39 Wellington Street, Central, Hong Kong

Tel: (852) 2522 5054 Fax: (852) 2877 0860

austcham@austcham.com.hk www.austcham.com.hk

Assistant Secretary, Personal and Small Business

Tax Branch

Personal and Indirect Tax and Charities Division,

The Treasury

Langton Crescent

PARKES ACT 2600

By email: individua[email protected]ov.au

22 September 2023

Dear Sir / Madam,

Consultation on modernising individual tax residency

We write on behalf of the Australian Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong (“AustCham”), in

respect of the July 2023 consultation on the proposed changes to the Australian individual tax

residency rules (the “New Residency Rules”). The consultation relates to changes that were first

announced by the then Government in the FY20/21 Budget following a review of the Australian tax

residency rules by the Board of Taxation in August 2019.

Our submission is focussed on ensuring that Hong Kong based Australians and Australian

businesses operating in Hong Kong are on a similar footing (or at least no worse off) than

Australians residing in jurisdictions that have concluded a double tax agreement with Australia.

The Consultation outlines the background to the review that was undertaken by the Board and

their recommendations to modernise and simplify the current residency rules. The proposed

changes are designed to ensure that the tax residency framework is consistent with the principles

of adhesive residency, certainty, simplicity, and integrity.

When the proposed changes were first outlined back in 2019, we had the opportunity to engage

with various arms of government, including Treasury, outlining our views as well as highlighting

several areas of concern that the changes could have for many expatriates, but especially for

Hong Kong residents.

At that time, we expressed our support for the stated aims of achieving simplicity in determining

tax residency and greater certainty for globally mobile individuals and their employers. However,

P a g e 2 | 14

there were several real concerns over the harsh adverse impact that the proposed changes could

have on Australian businesses and individuals living in Hong Kong and elsewhere in Asia.

In particular, we highlighted how adverse the amendments will be for Hong Kong based

Australians and Australian businesses operating in Hong Kong. Hong Kong plays an important

role as a global financial centre as well as regional headquarters and trading hub for many

Australian businesses. There are approximately over 100,000 Australian nationals living in Hong

Kong, many of whom would travel frequently to Australia for work and leisure,

This number of businesses and Australian individuals demonstrates that Hong Kong tax residents

will be uniquely impacted by these new residency rules more so than perhaps any other

jurisdiction given that there is no double tax agreement in force between the two jurisdictions

(unlike the other jurisdictions with high number of Australia businesses and individuals being

Singapore, the United Kingdom, and the United States). Australian citizens and permanent

residents living and working in Hong Kong (irrespective of the duration that they have lived outside

Australia) are likely to be severely impacted under the proposed changes.

The new residency rules, as currently proposed, will result in an inequitable outcome for Hong

Kong based employees. This will be adverse to Australian businesses as it will materially impact

their ability to attract staff and executives to Hong Kong. It follows that this will have a significant

adverse impact on the role and influence of Australians in the region at a critical time, when

continued deep engagement on the ground is required.

The consultation outlines the proposed framework for the updated tax residency rules as well as

requesting feedback on a number of specific aspects of the proposed changes. Encouragingly,

many of the questions for comments relate to the issues we have raised with various members of

the Government during the consultation that occurred back in 2021. However, despite the

concerns that were highlighted back in 2021, the proposed tax residency framework outlined in the

consultation remains unchanged from what was first proposed. This is disappointing.

Summary of substantive change requested

It is AustCham’s submission that the inequitable outcomes, based merely on whether there is a

double tax agreement with that jurisdiction, should be addressed through the introduction of a tie

breaker test, similar to OECD Model Tax Convention on Income and Capital, where the

Secondary Test applies.

The tie breaker provision ensures that individuals that are genuinely tax resident in another

jurisdiction are not discriminated against and unfairly treated resulting in double tax based merely

on their home jurisdiction. This discrimination and inequity will be experienced by those

individuals that live and work in Hong Kong as it does not have a double tax agreement with

Australia and is not expected to finalise one with Australia in the immediate future.

P a g e 3 | 14

It is acknowledged that the introduction of such a tie breaker would, in part, be contrary to the

Government’s current position on the implementation of residency not being aligned with

outcomes under a double tax agreement

1

. However, the tie breaker test is well understood by the

ATO and tax advisers and would not, as asserted, make it more complicated for taxpayers.

Indeed, it would allow for clarity on a taxpayer’s residency if that individual were a genuine tax

resident of Hong Kong (or another jurisdiction).

The Secondary Test, if adopted with or without amendments (which may increase the complexity)

such as the exclusion of days, even an increased number of days, or different or additional

factors, will distort how an individual will conduct themselves and their affairs if they move from or

to Australia.

Key features of the changes

The consultation outlines the key features of the changes to the residency rules, which remain the

same as the proposals announced back in 2021 as recommended by the Board. The New

Residency Rules framework has the following features:

- Physical presence in Australia being the primary measure of residency, on the grounds

that this would be aligned with international practice.

- The rules will focus on a connection with Australia; and

- The rules will apply additional factors to be determined objectively whether a person

would be considered a tax resident or not.

Based on these features, the proposed changes will involve Primary and Secondary tests.

● The Primary Test

The Primary test being that if a person was physically present for 183 days or more in

Australia in any income year, that person would be considered to be a tax resident of

Australia. In addition, if a person is physically present in Australia for less than 45 days in

any income year, they will be deemed to not be tax resident.

● The Secondary Test

The Secondary Test gives rise to the greatest number of concerns. The Secondary Test

will apply where a person is in Australia for between 45 and 182 days for whatever reason.

Under that test, if 2 out of the 4 secondary tests were satisfied, then such persons will be

considered tax resident in Australia – subject to the application of any applicable

comprehensive double tax agreement that may be in force with Australia.

1

Paragraph 62 of the Consultation Paper

P a g e 4 | 14

Our concerns therefore remain, for many Australians living and working in Hong Kong, the

test will ultimately become a ’45-day rule’ as persons are likely to easily satisfy 2 out of the

4 tests. As such, Australian nationals living and working in Hong Kong will be at risk of

being Australian tax resident if they spend more than 45 days in Australia. This is why we

are of the view that Hong Kong will be uniquely adversely affected by the proposed

changes given Hong Kong does not have a double tax agreement with Australia.

Further, given Hong Kong’s role as a global financial centre, a trading hub for the region

and the gateway for capital flows to and from mainland China, many businesses require

their Hong Kong based employees to travel extensively, including to Australia. Hong Kong

is an attractive base for Australian businesses wishing to take advantage of the gateway to

China. It is unique in that Australian Business can second or relocate their Australian

based individuals to Hong Kong because the infrastructure (e.g. schools, language, legal

system, banking system, Australian teachers and curriculum) to support Australians living

in Hong Kong is not readily replicated in China or other Asian jurisdictions.

This could therefore seriously disrupt the way in which Australians and Australian

businesses in Hong Kong conduct their business dealings with China and Australia. It

would particularly impact businesses in the Education, Aviation, Tourism and Financial

Services Sectors, amongst many others.

Consultation questions 1 and 2. How many days in an income year should an individual

with strong connections to Australia be able to spend in Australia before they are

considered tax resident?

This is a particularly important issue for Australians in Hong Kong given the absence of a

comprehensive double tax agreement with Australia.

We acknowledge the comment in paragraph 62 of the consultation paper that the Government is

not planning to align the domestic residency rules with outcomes under the double tax

agreements, despite the Board of Tax’s recommendation, on the basis that it would make it more

complicated for taxpayers. We do not agree that such an adoption of the tie breaker would make

it more complicated for taxpayers. Indeed, we are of the view that the adoption of the double tax

agreement position makes the new test equitable and simplifies the potential application of these

new provisions.

We are of the view that for Australian nationals that are tax resident in Hong Kong, the rules

should apply a tie breaker test for such persons. That is, Hong Kong tax residents should be able

to spend up to 182 days in Australia before they are able to be considered tax resident, provided

they satisfy a tie breaker test. The purpose of the tie breaker test is to align Hong Kong tax

residents with Singapore tax residents, who will benefit from the double tax agreement with

Australia (and residents of other jurisdictions with a double tax agreement with Australia). This

P a g e 5 | 14

would allow Australian businesses to allow their employees to travel to and from Australia for work

purposes, whilst allowing Australians to continue to visit family and friends in Australia.

The tie breaker test could be introduced as part of the legislative amendments to the residency

rules and would effectively operate, if the Secondary Test applies, to test if that individual is a

genuine tax resident of another jurisdiction, We believe that this would be a simpler, and equitable

solution to what would otherwise be a significant problem for Australian businesses (as an

Australian business or individual should not be treated differently merely because of the

jurisdiction within which they reside. We would recommend that the tie breaker be consistent with

the OECD Model Tax Convention on Income and Capital

2

, which is widely adopted, and it would

provide an objective and well understood test for those individuals with legitimate claims of tax

residency elsewhere, such as in Hong Kong.

Consultation question 2. Should some days spent in Australia under circumstances be

disregarded for the purposes of the 45-day count?

We firmly are of the view that the 45-day count is unworkable as it would easily result in many

foreign tax residents becoming Australian tax residents merely from carrying out their regional

employment duties as well as visiting family and friends. As explained above, for persons that

have established a genuine tax residence outside of Australia, the threshold must therefore be

increased to a more reasonable limit – say,182 days.

In the absence of a tie breaker provision, the proposed day count would somehow need to take

into account the nature of the visits, and therefore some visits would need to be disregarded for

the purposes of the count. However, we acknowledge that having a rule that excludes some days,

will involve an element of subjectivity (requiring supporting materials), that could lead to

uncertainty and perhaps even challenge. This would not be in line with the purported objectives of

simplicity and certainty.

Disregarding days could be done in one of two ways, but both of these could result in unwanted

complexity. For example, the framework could disregard days for employment related duties

where there is no nexus with a permanent establishment in Australia. Alternatively, non-workdays

could be excluded so that visits to Australia for holidays or to visit family and friends are not taken

into account for the purposes of the 45-day rule test.

As you will appreciate, both alternatives may give rise to some level of judgement and therefore

some uncertainty and a blurring of the lines between whether a day in Australia was for one

purpose or another, together with how an individual is able to support an assertion that a day is

outside the relevant count. Accordingly, consistent with the themes of simplicity, certainty, and

integrity we recommend a tie break type provision be introduced into the legislation such that a

2

See Article 4 of the OECD Model Convention with respect to Taxes on Income and Capital (2017)

P a g e 6 | 14

person with a genuine tax residence, say in Hong Kong, would have a day limit of 182 days before

becoming an Australian tax resident. As mentioned already, the inclusion of the tie breaker

provision would be in line with international best practice and provide all individuals equitable

treatment in determining their Australian tax residency.

Consultation questions 3, 4, 5 and 6. Could any of the four factors be defined differently?

Are there any other factors better suited to identifying individuals with strong

connections to Australia in an objective and simple way?

Although the intention of the changes is to simplify the criteria of when an individual will be treated

as an Australian tax resident, the effect of the proposals announced is likely to result in Australians

living and working in Hong Kong and elsewhere in Asia for many years being Australian tax

residents going forward. The concerns stem from the construction of the Secondary Test of the

New Residency Rules, which considers not just physical presence in Australia but other factors.

Indeed, these other factors are such that most Australian nationals would easily satisfy at least

two of the tests.

Under the proposed rules, Australian nationals and permanent residents can be treated as tax

resident if they are physically in Australia for 45 days or more in a year if they also satisfy two out

of the four additional substantive ties or nexus factors outlined in the framework. Broadly, the four-

factor test, for Australian nationals or permanent residents, is, for pragmatic purposes, a one

factor test. The other three factors follow themes in the OECD Model Tax Convention on

residency for individuals but implement a threshold at a much lower level such that genuine

foreign tax residents are likely to satisfy two of the four factors. The other three factors are:

● Australian family connections;

● the ownership of property in Australia and having a legal right to access such

accommodation; and

● other Australian economic interests, which include participation in a business or even a

bank account with ‘significant’ cash in the account.

Simply being an Australian national or permanent resident and either having a dependent living in

Australia or a property available for use in Australia would satisfy two of the conditions. The ease

with which many Australians would therefore satisfy these additional factors means that the